As a longtime veteran of public schools, Kent Swinson remembers all too clearly earlier days of drastic school funding cuts. But he says he’s never been as discouraged as he is today.

The difference is you always hoped you saw some light at the end of the tunnel” in past budget crises, said Swinson, superintendent of Sparta Area Schools. “You just don’t, now. It just seems like when one negative thing happens, there’s one right behind it, and it doesn’t stop.”

The new negative for Sparta is a layoff of 29 employees, most of them teachers. The Sparta Board of Education approved the layoff notifications Monday night to help reduce a budget deficit of some $2.3 million.

Some of those laid off will be recalled but there will be a net reduction of about 20 teaching, counseling and other certified positions, Swinson said. After years of other cuts, consolidating services and private contracting, this is the first time the district has had to lay off teachers during his nine-year tenure.

“We’ve done so many things over the years to try to avoid those cuts in instruction that we probably have done too good a job of it,” Swinson said. “Now we’ve come to a point where there’s no place else to go.”

His district is far from alone. It’s feeling the pain of classroom cuts other local districts already have endured – and still must.

Schools face common funding woes

“What you’re seeingin Sparta is a story that’s been told all across Kent County,” said Ron Koehler, an assistant superintendent for the Kent Intermediate School District.

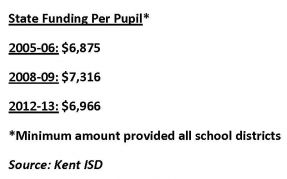

The county’s 20 districts all are contending with rising costs and stagnant state aid. State per-pupil funding this year is down nearly 5 percent from 2008-09 and only 1 percent higher than seven years ago.

All but three districts had to cut teachers and other staff between 2009-10 and 2011-12 (see chart). In that three-year span, districts reduced their full-time equivalent employees by 608, including 261 teaching positions. (When Kent ISD staff cuts are added, this total reaches 680.)

The misery is being shared by wealthier and lower-income districts alike. East Grand Rapids faces a deficit of $1.5 million and is contemplating cuts from elementary art and paraprofessionals to increased pay-to-play fees.

“For most districts, this is the year we’re out of options,” said EGR board member Elizabeth Welch Lykins. “There’s nothing left to cut. It’s coming into the classroom this year, everywhere.”

But schools aren’t taking the trend lying down. Parents are teaming with school officials to push for more state funding for their increasingly strapped districts. They say they are fed up with legislators who say they support education but don’t put their votes where their mouths are.

“Parents have to become advocates for their children now, because superintendents alone can’t do it,” said Lykins, a mother of two students. “They need hundreds of thousands of parents saying, ‘Enough is enough.’”

Pushing for change in Lansing

More parents are speaking up through groups such as Friends of Kent County Schools, a private lobbying group in which Lykins is active. She also is a board member of Michigan Parents for Schools, a statewide group whose president, Steven Norton, last week sent an open letter to U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan. It charged key state policy makers are pursuing “an extremely narrow and barren notion of ‘education’ (based on) the lowest cost possible.”

Local school officials fear some lawmakers are pushing privatization by reducing public funding of education. They say parents need to press legislators to restore earlier levels of funding, because schools have already made major cuts and streamlined services.

“I have never seen it this difficult in 38 years in education,” said Mike Paskewicz, superintendent of Northview Public Schools, which has cut nearly $3 million from its budget since 2008.

Officials say the roots of the problem go back to 1994, when voters approved a landmark reform of how schools are funded. By shifting the burden of school funding from local property-tax millage to an increase in the state sales tax, Proposal A was meant to provide more stable and equitable school revenue. But by putting a ceiling on school millage rates for operating purposes it also prevented districts from going to voters when funds ran low.

Higher costs, less money

That shift started creating big problems for schools when the state economy began to nosedive in 2000-01. The subsequent recession, massive loss of jobs and lower housing values meant lower tax revenue for the state and less aid for schools, said Craig McCarthy, Northview assistant superintendent for finance and operations.

Per-pupil state aid payments peaked at $7,316 but were cut to $6,846 for the 2011-12 school year. The payment increased to $6,966 this year, but Northview stands to lose anywhere from $2 to $34 per student under current state proposals, McCarthy said.

Meanwhile,districts face soaring health-insurance and retirement costs. As charter schools and privatized services have drained employees from the public schools, those who remain must pay higher rates, along with the school districts. Northview’s costs jumped by $700,000 between 2008 and 2011.

The district has coped by eliminating its high school block-scheduling program, cutting staff and delaying bus purchases. This year is the first time since Paskewicz arrived in 2009 that he has not had to make layoffs.

Those kinds of reductions are typical of how districts have responded to calls for belt-tightening during the recession, said Koehler of Kent ISD. “Still, I don’t think there’s anybody in the county who wouldn’t say we’re well beyond the fat and into the bone,” he added.

Trying to spare the classroom

In Sparta, officials have made efforts to spare students and teachers from cuts in recent years, Swinson said. They have privatized busing and custodial services, drawing protests from some residents and workers, and trimmed administrators.

But a sharp drop in migrant students last fall due to the West Michigan crop failure contributed to an enrollment loss of 113 students and a deficit of $2.3 million. There was nowhere else to cut but the classroom, Swinson said.

All teachers with fewer than five years’ seniority will be issued layoff notices. Meanwhile, negotiations for a new teachers contract begin this week, injecting more uncertainty into the budget picture.

“We’re operating on the revenues we were receiving back in 2005-06,” Swinson said. “I don’t think very many homes could survive doing that.” It’s a sad scenario after seeing so many past funding crises, said Swinson, who is about to retire after 37 years in education.

“To be honest I never thought we would get to this point,” Swinson said. “But it just keeps coming.”

CONNECT

To contact legislators or concerned parents, go to www.miparentsforschools.org or https://sites.google.com/site/friendsofkentcountyschools/Home