Editor’s note: Teachers have strived for years to improve the math performance of American students, who consistently test below the average of other developed countries. This week, School News Network begins a multipart series on why so many area students struggle with math, and what teaching methods are proving effective in helping students to excel.

Teacher Eryn Welch sat on the floor with two second-grade boys who looked a little bored. Before them were paper and pencil, two wooden blocks, dice and a banner of numbers taped to the carpet.

Early one morning at North Godwin Elementary School in Wyoming, these were Welch’s tools for one of the toughest tasks in education: teaching math.

In a school where many students excel at numbers, Welch was hired to help those who don’t. Today she would work with 20 students two-by-two, her small part in the big challenge of improving student math performance in Kent County schools.

“All right, ready?” she asked Desmond Long. “What number are you starting at?”

“One hundred twenty,” Desmond said, writing it down. He rolled a seven with his dice and counted down aloud with his fingers until he reached 113. “Check your work,” Welch said. He moved his wooden block over the numbers on the banner, stopping at 113. “Good job,” Welch said, giving him a high five.

Count it as one small success for one student. But Kent County needs countless more high-fives if students are to be ready for college and career.

Fewer than half of the county’s public elementary students are considered proficient in math on standardized tests. It gets worse from there, falling to one-third of high school juniors or seniors scoring as proficient.

Kent County is far from alone, however: Michigan ranks below national averages in math testing — just as U.S. teens trail those of other developed countries.

But high-performing schools like North Godwin buck the trend. They show it’s possible to not only teach students equations but the real-life application behind them.

“To help the kids become better thinkers: That’s the goal,” said Principal Mary Lang. “They have to be able to think through and process, not just regurgitate information anymore.”

Scores Drop in Higher Grades

Teaching students to understand the concepts behind computation is key to improving their performance, many educators agree. In several schools, teachers are finding creative ways to make math add up for their students.

“Math is the way we make sense of things that happen in the world,” said Allison Camp, a math consultant for the Kent ISD who coaches teachers on effective methods. For too many students, however, math doesn’t make sense at all. And the higher their grade level, the less sense it makes.

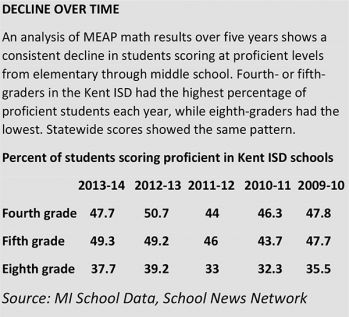

The Michigan Educational Assessment Program (MEAP) measures math achievement for students in third through eighth grades. In a School News Network analysis of MEAP results over the past five years, math scores steadily declined as students moved up from elementary through middle schools (see graphic).

At the high school level, roughly one-third of students scored proficient on the Michigan Merit Examination measuring state expectations for math. On ACT scores, 40 percent or less scored high enough to be considered as having a good chance of success in college math.

Camp says scores plummeting in middle and high school is a national problem. A major reason, she says, is that students learn addition, subtraction and other procedures at a “surface level” but not the deeper logic. As they ascend through the grades the procedures pile up — and so does students’ confusion.

“It’s like every year is just about learning a new set of rules instead of learning about the big idea,” said Camp, a former high school math teacher. She compares it to driving in a strange city without a GPS then hitting a road block: “If I have no sense of where I am, I’m stuck.”

Some Districts See Success

Long before students are old enough to drive, however, they pick up messages about math, noted Camp. “No parent will show up to a parent-teacher conference and say, ‘I was never a good reader,'” unwittingly suggesting that not being good at math is more acceptable.

Further, if young students don’t read as quickly as classmates, no big deal. They’re still reading. But if they don’t add quickly, they may feel judged for being slow. “Kids get a sense very early on whether they’re good at math or not,” Camp said.

Given these challenges – and the fact academic achievement tends to reflect family income – some districts are tackling the big math problem with relative success.

Byron Center Public Schools had some of the best MEAP math scores in the Kent ISD this year, including the highest proficiency of all 20 districts in fifth and sixth grades. A district instructional specialist credits a few basic strategies — like making sure students spend enough time on math – for much of that success.

“It sounds very simple, but when you have an assembly or an art project it’s very easy to say, ‘OK, we’re not going to get to math today,'” said Kari Anama, executive director of instructional services. “There’s a real cognizant effort to make sure we’re teaching math at least an hour a day.”

The district also has initiated Professional Learning Communities, where teachers gather weekly to compare notes on what’s working and dig into data to pinpoint problem areas. “We’re always looking at, is there a gap somewhere?” Anama said. “Is there something we’ve missed?”

In Byron Center and other districts, teachers also have begun using the Common Core State Standards, a national set of learning objectives. In math, the standards focus more on foundational skills in early grades and emphasize the underlying concepts and real-world applications. Over time, Camp says, it should improve student performance in higher grades.

Small Groups Produce Big Benefits

Small Groups Produce Big Benefits

For now, Camp sees the most promising results when teachers turn over more control to their students working in small groups: “You learn more about the kids’ thinking that way.”

Back at North Godwin Elementary, teachers have seen strong results with that approach as well as the two-by-two instruction provided by Eryn Welch.

Its third- and fourth-graders made substantial gains on their MEAP scores this year, with 87 percent of fourth-graders scoring proficient. Scores were well above Kent ISD averages even though the school has a high percentage of low-income and English-learner students.

“We’re proud of those scores and having those kids do so well,” said Lang, the principal, adding the scores reflect an increased emphasis on math.

Superintendent William Fetterhoff said schools have been “remiss” in focusing more on reading than on math. He attributed North Godwin’s success to strong leadership, close tracking of data and teachers willing to “look beyond their own egos” to see what’s working in other classrooms.

“We’ve been a closed-door profession for so long — you go into your classroom and close the door and have your own little world in there,” Fetterhoff said. “We needed to form learning communities with teachers. The old adage says two heads are better than one, and we finally embraced that.”

Last year North Godwin used state funds to hire a specialist who works with students needing extra help. Welch meets separately with two students from each second-, third- and fourth-grade class, focusing on weak spots found in test scores. A problem for many is impatience, she said: “If they don’t get it, they get frustrated and just guess.”

She worked on that with Desmond Long when he miscounted a subtraction problem. “You counted really fast,” Welch told him. “Slow down. Think about it.”

Later, she helped students prep for a test in Lisa Koeman’s second-grade class. Koeman had split the class into rotating groups of four or five, where they quizzed each other on vocabulary, calculated the dimensions of a farm and designed their own dream houses.

As Julio Villeda drew up his house, he said he likes math the way he likes solving puzzles. “It makes you smarter,” he said. “I get into it.”

Koeman hopes her activities help other students find a reason to learn math.

“Giving the real-life situations helps them connect,” Koeman said. “It gives them that ‘why.'”

The more students can make such connections, Camp said, “Maybe math then wouldn’t be that class where kids go, ‘Why do we need to learn this?’ “

Linda Odette contributed to this report

CONNECT

MEAP math scores for Kent ISD schools