When Paul C. Gorski wants to illustrate stereotypes about poor people, he looks no further than his own grandmother.

Though she grew up poor in an Appalachian coal-mining town, Grandma Wilma was her class valedictorian, matriarch of her family and spiritual core of her community. Yet people made unflattering assumptions about her because of her clothing and her speech, said Gorski, who writes and speaks about school bias against the poor.

“Watching that growing up was heartbreaking,” Gorski recently told a group of Kent County educators. Today, he added, “low-income students experience that same thing all over this country.”

But like his grandmother, poor students possess resilience and resources that can help them succeed in school, Gorski said in an Aug. 14 talk for the Kent ISD Diversity Initiative. But teachers first must put aside deep-seated misconceptions about the “perceived deficiencies” of poor families, Gorski argued.

“If I grow up in the United States, I’ve been socialized to misunderstand the experiences of people in poverty,” Gorski told 200-plus educators at Ottawa Hills High School. “Ninety-five percent of this is pushing those stereotypes and biases out of our minds, and replacing it with a deeper, more compassionate understanding.

“What we don’t want to do is (imagine) solutions that are all about fixing poor people, rather than fixing the things in our schools that marginalize poor people.”

Myth of the ‘Great Equalizer’

Gorski forcefully lays out the case for better serving poor students in his 2013book, “Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap.” He is an associate professor of integrative studies at George Mason University and the founder of EdChange, a website dedicated to building more equitable schools and communities.

He spoke as part of the Kent ISD’s ongoing Diversity Initiative aimed at creating more inclusive and equitable schools. Training in the Global Champions program adopted by Forest Hills Public Schools is being offered to educators this school year. Forest Hills students touted its benefits prior to Gorski’s talk.

In sometimes blunt terms, Gorski said it is not poor students’ deficiencies that primarily limit their academic achievement. Rather, he said, “It’s about the stereotypes and biases that even the most well-intended of us have about low-income students and their families.”

Criticizing reformers such as Ruby Payne for attributing the achievement gap to the culture of poverty and “hidden rules” of class, Gorski asserted myths about poverty hinder teachers and damage students. Contrary to popular belief, U.S. schooling generally reinforces society’s inequalities, he told educators.

“We call it the great equalizer, even though the school system is set up basically to reproduce the social conditions that already exist,” said Gorski, who also led two workshops for teachers.

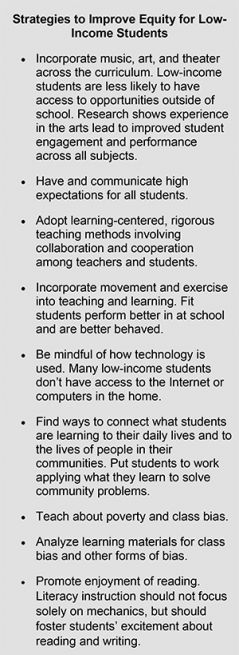

He argued schools perpetuate inequity for poor students with inadequately funded schools, larger class sizes, lower-paid teachers and less access to resources like school nurses and well-stocked libraries. Further, low-income students have less access to preschool and preventive health care and are more exposed to environmental hazards.

“These conditions do not reflect or result from low-income families’ ‘cultures’ or attitudes about education,” Gorski writes.

Dump ‘Deficit View’ and Recognize Resiliency

Unfortunately, Gorski said, educators are just as subject as others to stereotypes that poor people are bad parents, don’t care about education, don’t work as hard and don’t have good role models. They may assume a mom didn’t show up for a parent-teacher conference because she wasn’t interested, when in fact she may have had to work.

“If you believe that poor people are poor because of their own deficiencies and not because of structural barriers, you are likely to contribute to the very inequities we’re trying to eliminate,” he said.

Though most teachers are “super well-intentioned,” Gorski said in an interview, many lower their expectations of poor students because they view them as broken and deficient, thinking, “’I don’t want to be too hard on these students because they must have a very hard home life.’”

On the contrary, he said, research shows low-income students and their families possess many strengths such as resiliency, generosity and more ability to handle stress than wealthier people. But too often they’re stuck in schools that lack the best means for improving their performance, such as art, music and physical education programs.

Gorski calls for an “equity literacy” approach that recognizes poor students are as diverse as their classmates, that presumes test scores don’t accurately measure equity and that demands teachers offer the same high expectations and teaching methods students get at wealthier schools.

“They should see all their students as individuals, seeing the strengths and gifts that each of them bring,” Gorski said after his talk. “Many of them have had some challenges outside of school because of inequality. Appreciate the resiliency they’ve had just to get through that and still be in the room.”

Omar Bakri, principal of Crestwood Middle School in Kentwood, said he likes Gorski’s approach, noting he and his staff continually tell students they are smart, capable and will achieve with hard work.

“Perception really gets in the way of learning,” Bakri said. “The difference between a biased and unbiased teacher is astronomical. When you have higher expectations the kids rise to it.”

CONNECT