Some years back on a Fourth of July, schoolteacher Sarah Bolema fielded a phone call from a distraught student’s mom. To the mother’s horror, her son was acting out his anger by climbing onto a dangerously steep roof and refusing to budge.

Bolema asked the mom to toss the phone up to her kid, where the teacher then talked him down to safety. Later, she asked the mom, “Why didn’t you just call the police or the fire department?”

And the answer is this:

Sarah Bolema is the fire department. And the police department. And a social worker. And a psychologist. And philosopher. And negotiator. And facilitator. And a bridge builder and a miracle worker.

Sarah Bolema, in fact, may be among the most capable and compassionate teachers you could ever meet. And it’s not just because she excels at helping her fifth- and sixth-grade special needs students soar.

This educator from Wyoming Intermediate School makes everyone around her a better person, and let’s face it, you can fit the number of those people in our midst on the head of a pin.

When she’s not shepherding the 16 kids who call her teacher, she’s caregiver to husband Chad, who’s challenged with multiple sclerosis. Her mother has cancer and is undergoing chemotherapy. Sarah battles her own blood disorder, which ravages her with blood clots. She has taken in an older sister who has cognitive and health issues. She calmly fields questions from folks who wonder why she and her husband, both white, have an African-American daughter.

Then there are all the other kids and teachers at her school who look to her for advice, mentorship, direction, hugs.

Oh yeah, I almost forgot: She also teaches night school at Grand Valley State University.

I spent the better part of a day in Sarah’s classroom, and refreshingly, she had but scant seconds to spend with me.

That’s because she was too busy loving on her children who present cognitive and emotional impairments, literally twisting and turning in every direction to answer their needs.

And the sweetest lesson I learned that day had nothing to do with reading or math. It occurred when Sarah noticed a little boy with his head in his arms.

She drew near and whispered, “What’s wrong?” And he answered, “I miss my daddy.” Together, they figured it out.

You want to complain about teachers or the state of education? You’d be hard-pressed with Sarah Bolema stories in your pocket. Although Sarah herself wouldn’t be offended. She’d just remind you that it’s never too late to go back to school for a teaching certificate, and “if you can do it better, then please, go for it.”

That’s Sarah’s World – a complex but pragmatic approach to figuring out everything from your next move to your next year, relying on a formula that demands you work hard, take nothing for granted, and accept the distinct possibility that life will hand you some nasty curves.

Though she never brought it up, I learned Sarah is the first to visit a sick kid in the hospital. She makes home visits too. And recently, she babysat for a young man in her class who was too sick to attend the football game where his sister was eventually crowned homecoming queen. The rest of the family was able to go because Sarah gave up her Friday night for them.

I ask you, how many teachers do you know who will routinely spend time with their students on a weekend? Or host a monthly “Family Night” for kids and their parents, grandparents, guardians, whoever’s hungry?

And while most teachers spend about $500 each year on their classrooms, how many use upwards of $2,500 of their own money? Spent on everything from shoes to backpacks to – and I witnessed this – subtly handing out breakfast cereal so kids have something in their stomach that night.

How many teachers – how many people – do you know who only weep for others, and never for themselves?

“In 17 years,” says good friend and colleague Chrisi Karas, who works down the hall from Sarah as a social worker, “she has never raised her voice or lost her cool. And she never cries for herself.”

Chrisi pauses. “OK, once,” she tells me, “on the day you were coming to visit her, because she was afraid of what you were going to see.” “‘I’m just a regular person,'” Sarah had blubbered to Chrisi.

Hardly.

The day begins with what Sarah dubs “Morning Check-in.” It’s an opportunity for her kids to share what’s happened since she last saw them. “I know that for some, Mondays are really rough, because they were with a particular parent the night before.”

She looks for kids biting their nails. Staring her down. Looking away. Complaining of a stomachache. A bully. Another teacher. Was there an incident on the bus, at home, at the mall?

“I look for patterns,” she says. “Clues. Like people who play cards.”

Art instructor Shawn DeJonge teaches right across the hall. Sometimes he sends his kids into Sarah’s room, because he knows Sarah will help them decompress, cool down.

“She’s great at de-escalating a situation,” he says. “And her heart is huge. She’s just a big believer that we’re all here to take care of each other. She feels an obligation. But it’s completely out of love.”

Shawn remembers first meeting Sarah, and being in awe of the way she managed her kids. “I found myself watching her, to learn what she does naturally. She’s a can-do person. ‘No’ is not the answer. Instead, it’s ‘We’ll figure this out.'”

Kathy Meredith is a paraprofessional in Sarah’s classroom. She’s privy to the same things Sara is – which kids are homeless and bouncing around from friend to friend or among relatives. Who’s always hungry. Who looks afraid.

“I don’t know how she does it,” says Kathy. “She’s gotten pneumonia the last three years, but she refuses to stay home. It’s all about ‘Who’s gonna help my students?'”

Kathy has lost count of the number of times Sarah has accompanied kids and their parents to the doctor, a psychologist, psychiatrist. She tracks an inordinate number of kids who are on meds, use inhalers, can’t remember which bus, lose their homework, need things repeated, have trouble focusing, crave another’s gentle touch.

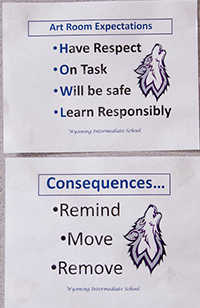

The poster on the door to her room speaks volumes: “Be responsible. Anything else is despicable.” On a nearby wall, you’ll read that “Fair isn’t everybody getting the same thing. Fair is everybody getting what they need to be successful.” And this as well: “Do the right thing even when no one is looking.”

As I enter the room, one at a time, more than half the kids rise and stroll over to greet me with a handshake. In the next instant, they’re learning. Some will watch a video. Others read. Others write. Still others are on headphones and linked to computer stations.

The room is a cornucopia of stimuli: Charts, graphs, images, safety signs, art work. A “social contract” reminds students to “be a role model…be respectful…stay in line…be on time…hands to yourself…be nice.”

I notice that Sarah’s hair is swept back, and I write in my notebook that “Of course it is. She doesn’t have time to even brush it off her forehead.”

Carli Geers is a graduate psychology student at GVSU and in Sarah’s classroom once weekly to mentor and learn. “I think Sarah does a fantastic job of engaging these kids, of motivating them,” she says. “And the kids are so kind to each other,” she adds, slowly giving “kind” two syllables. “Theyalways seem so eager to go out of their way to help someone else.”

Well, they’ve got a great person to model.

After school, Sarah fills bags with books – and treats – and heads over to Anthony LeMieux’s home. He’s a 13-year-old student too sick to attend school, so Sarah’s tutoring him where he lives.

Another student – Ethan – is along for the ride because he’s developed a close friendship with Anthony.

Anthony suffers from dyskeratosis congenital, a rare and progressive disorder that has landed him in hospitals more times than any kid should. He’s just returned from a 10-day stay at Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital, and he’s learning to adjust to a titanium rod recently implanted in his left leg.

I ask if he has doctors at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. His mother Heidi smiles. “Seven or eight.”

Sarah’s presence is a relief to the LeMieuxs, who try to balance the rest of their lives with caring for their Anthony. Heidi seems to relax as Sarah strolls in and gently takes over. “She’s phenomenal,” says Heidi, echoing a word I’ve heard all day long to describe this humble special ed schoolteacher.

Anthony and Ethan chow down on doughnuts as Sarah tries to conjure cooperation from a laptop. Anthony is amused, and Heidi clasps her hands and says, “That’s the first time I’ve seen him smile all day.”

Heidi knows of Sarah’s own health issues, and that of her husband’s. She gazes over at Anthony and speaks to her own son’s prognosis, and of how it must be for Sarah and Chad. “She understands,” she says.

Sarah and her husband are both 40. Even with his disability, Chad still works. Together, they’ve assumed a heavy debt covering the incidentals that get him to and from doctors in Ann Arbor twice weekly. Her dad died of a massive heart attack when she was 31. And older sister Connie, 46, has too many cognitive and medical needs for their mother to handle, so she now lives with Sarah and Chad.

For 14 years, Sarah’s taught a classroom management class at GVSU. She doesn’t focus so much on teaching (“That’s the easy part”), but on how well they get to know their students. “It’s all about how to establish relationships and how to handle kids who seem like they’re out of control.”

In what little spare time she has, you might find Sarah scouring a thrift shop for some kid without a coat or boots. The district provides her a stipend for students, but she reserves that so her kids will be able to afford a book to call their own.

She’s taught her entire professional career in Wyoming, but you might argue that she’s been a teacher a lot longer.

As a high school student at Wyoming Rogers, she once dressed down the district’s director of special education for the way in which her brother – who had special needs – was being treated. “I said ‘You ought to be ashamed of the education my brother’s getting.'”

Years later, a college graduate, Sarah stood before the same man, seeking a job, and remembering him telling her “You were all about what was supposed to be best for your brother.” Then he hired her.

She spent 13 years at Wyoming’s Taft Elementary in a resource room with students who were emotionally and cognitively impaired, autistic and beset with learning disabilities. “I loved it.”

She’s been six years in the Intermediate building, where by all accounts, she is beloved.

She’s inventive beyond most, and when she suspected a student of some bad behavior in the community, she cleverly got him to confess.

By calmly coming to class one morning with a little cup of Mountain Dew, she prompted him to confess he’d been urinating on motorists from an overhead bridge. The cup was covered with plastic wrap and, when the kids inquired about it, she said that she was cooperating with her sister, a Wyoming police officer, to identify the culprit. This, she said, was a urine sample taken with a syringe.

By calmly coming to class one morning with a little cup of Mountain Dew, she prompted him to confess he’d been urinating on motorists from an overhead bridge. The cup was covered with plastic wrap and, when the kids inquired about it, she said that she was cooperating with her sister, a Wyoming police officer, to identify the culprit. This, she said, was a urine sample taken with a syringe.

That same day, the student she suspected stepped forward. “You got my DNA,” he said.

Chrisi Karas, the social worker, figures she and Sarah could write a book. They’ve been promised by higher-ups they will never work at different schools, so they’re in it together for the long ride.

“She is the epitome for individualization,” Chrisi says of her friend. “She meets their needs, not hers. And she never waters down, never dumbs down. In fact, she raises the bar higher. Her belief is that life is going to be hard for them, so how is this going to work for you.”

As a social worker, Chrisi’s seen a lot of kids, including one who approached her and asked something, well, phenomenal. Though he did not have special needs, he’d witnessed the magic emanating from Room 109.

And he was just wondering, “How do I get to be in Mrs. Bolema’s room?