Libby Metiva’s seventh-graders were spread out in her classroom and the adjoining hallway, working in small groups on the answer to a science experiment: Why did an egg immersed in corn syrup shrivel?

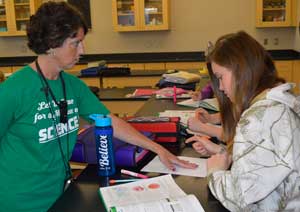

Some students just weren’t getting it. Metiva pressed one of them to figure it out.

“Cells need water to live,” she explained firmly. “Osmosis is a process involving water. What happened to cause the egg to shrivel?”

“It was dehydrated,” the boy replied.

“What left the egg?” she persisted.

“Water,” he said, correctly.

It was the kind of critical thinking she aims to activate in her students at Cedar Springs Middle School. On this day, 32 students still sluggish from four days of standardized testing weren’t lighting up the room. Metiva kept them overtime to dig for their own answers.

But even the slow-learning days are gratifying for Metiva, a high-energy science teacher who just completed her 20th year at Cedar Springs Middle. She loves the curiosity and humor of her students, and awakening them to the marvels behind something as simple as why an egg shrinks in Karo syrup.

“Science is all around you, all the time,” Metiva said before class. “What I want is for them to look at life and what occurs around them with a sense of wonder.”

She also wants to give emotional support to young people making the vulnerable and difficult transition from childhood to adolescence. As the mother of four boys, she knows that passage all too well.

“They just want to be loved,” she said of her students. “It gives me the ability to mother a lot of kids.”

Feeling a Calling to Teach

Metiva has been teaching and loving students for 25 years, including five in St. Johns Public Schools. It was a natural profession for a woman whose father, Steve Ellis, taught for 37 years in Grand Rapids Public Schools and whose mother, Kathy, taught preschool.

<pdir=”ltr”>Her first interest was health care, however, and she considered the physical therapy program at Grand Valley State University after graduating from Rockford High School. But as much as she loved science, she disliked the idea of working in hospitals. Plus she loved working with young people, as a camp counselor in high school and as an Upward Bound counselor in college.

Teaching it was, then.

“Truly, teachers are called,” said Metiva, her blue eyes bright with conviction. “The best teachers really view it as their stewardship: This is my way to give back.”

For her, teaching is a way to give back to the excellent teachers she had, such as the fourth-grade teacher who challenged her with high expectations.

It’s also giving back to a community and school system she loves. The bond began when, just before her second job interview at Cedar, her fiancé was killed by a car. A school staffer called after the funeral to ask how she was doing, and said they would hold the interview until she was ready.

“I just won’t ever forget that grace and compassion,” she said warmly.

School is a Family

Metiva aims to show those qualities to her students, along with high expectations in teaching the latest science standards. She finds a perfect fit at Cedar Springs Middle, where teachers team up to teach subgroups of students in four “houses.” They work together to create content and address student behavior problems.

“Bottom line is, we love our kids. We’re a family,” said Metiva, adding Principal Sue Spahr is a “phenomenal” leader of the family.

Spahr returns the compliment, saying Metiva teaches with “energy and passion” and a gift for sensing students’ social and emotional needs.

“She truly listens with her heart,” Spahr said. “They know she loves them as a child first and as a student second.”

Metiva and her husband, Joe, saw many of her students grow up playing baseball with their sons and gave them treats at Halloween. Now she’s teaching them about photosynthesis and the 200 types of cells in their bodies.

“I have the luxury of playing Mom very easily with my (students) right now,” said Metiva, whose sons range from age 7 to 16. “That affords me a lot of grace. When I call them out on stuff, it’s very authentic.”

Metiva returned to the classroom three years ago after serving for five as an instructional coach supporting other teachers. She is happy to be back using the methods she shared with and learned from her fellow faculty, and to “just get to hang with kids” – about 130 of them a day.

“They’re full of energy. Their sense of wonder is so exciting. You break out the microscopes, and they will freak out over air bubbles on the slide.”

Two Screens: Academic and Emotional

She is acutely aware of all that those energized students bring: their disarming honesty and humor that cracks her up daily, but also their self-consciousness, their bodies growing out of their clothes and their sensitivity about being in or out with their peers. That means seeing them with a split screen, always ready to switch from their academic to their emotional needs.

“You’re delivering this content, but you also have an eye on how it’s rolling out – what kid didn’t get asked to be in a group?”

On the morning of the egg experiment, she did just that. When students split into small study groups, one girl was left sitting alone. Metiva found her a partner from a group of three.

But Metiva also demanded her restless students’ attention – “Let me see your eyes here” – as she methodically presented the day’s topic: what a cell is made of and what it needs to live. Using PowerPoint, handouts and textbooks, she had students read, discuss and write in their groups about what makes cells tick.

She roamed and listened, then brought them back together to share surprising findings, such as cells being about two-thirds water. Then she split them up again to reflect on the osmosis and diffusion evident in three eggs dipped in corn syrup, green water and Coca-Cola.

Tyler Harper said Metiva’s methods help him understand science, adding, “She likes to have it kind of perfect, presentation-wise.”

Addison Eckelbarger said although science is her worst subject, Metiva makes it easier by interacting with the students and requiring them to figure out the answers – even if it means being kept past the bell.

“If we can’t answer the question we’re not going to do good on the quiz, so then how are we going to learn?” she said.

That would please Metiva the teacher, who wants students to know what they’re capable of achieving. Metiva the mother would like them to remember something more.

“I would hope they would say I genuinely cared about them,” she said softly. “I would hope that someone would say they feel that I loved them.”

CONNECT