In Mary Lou Ohnsman’s class, the first step to learning handwriting is closing your eyes and putting your head down.

“See if you can visually see your first name in cursive,” Ohnsman tells her third-graders at West Oakview Elementary. “Visualizeit, because that will help you write it neatly.”

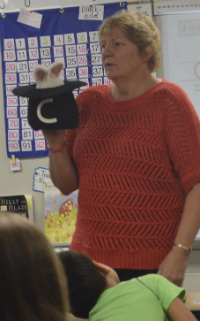

Then she gets out a top hat with “Magic C Bunny” popping out. He’s their helper in learning to write the magic c, which also helps them write the letters d, a, and g. She shows them how it works on an overhead: draw a c from the top line to the bottom, then straight up like a helicopter, back down like a ruler, then turn back up and aim for the corner – and there’s your g!

“I love making g’s like this,” says Aiden Obetts, drawing a bunch of them in his workbook. “It’s kind of fun making loop-de-doo’s.”

Magic c and loop-de-doo: It’s all part of learning to write in cursive, a requirement in the Northview district but falling from favor in many schools. It is not required by the Common Core, the voluntary national academic standards, and some question why students need to learn cursive when most of their work is done on keyboards.

Most states do not require cursive, but a handful have adopted curriculums that include it. In Michigan, which adopted the Common Core, cursive is not included in the English Language Arts Standards and its use is determined by local districts, said spokesman William DeSessa.

Northview students start learning cursive in third grade. For Ohnsman, in her 14th year of teaching, that just makes sense. It hones hand-eye coordination, and research shows it helps them retain information, she says.

“Keyboarding is fine,” Ohnsman says. “But when we actually do the handwriting, printing or cursive, it sticks in your brain better. It’s a slower process.”

Mixed Reviews by Pupils

She instructs them in cursive once a week for 20 to 30 minutes, teaching a new letter each week. Using their workbook, “Handwriting Without Tears,” students quietly work on their magic c’s, which help them write words like “cad” and “gag.” Ohnsman advises them on technique, like putting their forearm on the desk and relaxing their hand if it stiffens up.

Some, like Jillian Lopez, take pride in their penmanship.

“It’s different than regular writing, and they look cooler,” Jillian says. “I can do my name a little bit.”

Silver Crandell is having more trouble with it. “I like it, but sometimes it’s really hard and I get messed up,” he says, adding he doesn’t use it outside of school. “But my dad’s trying to teach me.”

Ohnsman likes the calm that comes over her students when they write.

“They chill, they relax, they like to do it,” she says. “It’s almost like a therapy. We take our time, we slow down.”

Plus, writing by hand puts students in a long tradition of human communication much more personal than email or texting, she says. “I hate to think about the day my daughter doesn’t write a card to me,” she adds. “We’re losing something.”

On the playground after class, she pulls aside some fourth-graders who learned cursive with her last year. They give it mixed reviews.

“It was either fun or annoying,” says Elliana Ramer, adding, “I’m better at writing than I am at typing.”

But Jordan VanRavenswaay gives cursive two thumbs up – or should we say five fingers. She loves to write, and last year turned in a handwritten, 147-page paper on soccer star Abby Wambach.

“I like how it makes it quiet in the room, so I can focus,” Jordan says. “It’s so calm. And it looks beautiful.”

CONNECT

Pros and Cons of Teaching Cursive