A fence illustration is often used to show the difference between equality and equity.

Two pictures each show three children, one tall, one short and one in between, trying to peer over a fence. In one picture, they are treated equally by standing on crates, but only two can see over. In the other, they are treated with equity, as the shortest child is given two crates to stand on, allowing him to peer over too.

The Achievement Gap by the Numbers:

|

On any given day in Godwin Heights, Wyoming, Grand Rapids, Kentwood and Godfrey-Lee Public Schools — diverse districts with high percentages of economically disadvantaged students — teachers are using a new approach to get all students looking over the fence, regardless of the barriers they face.

Fifty educators began in-depth training this summer through Leading Educators, a program designed to increase student achievement through teacher leadership and instructional practices.

They will continue the program over the next two years, the ultimate goal being to create equity in schools and close the achievement gap. The latter refers to disparity in educational performance among subgroups of U.S. students, especially groups defined by socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity and gender.

“We support teachers in holding up a lens that is focused on social justice and creating anti-racism systems and structures,” said Mary Kay Murphy, program director for the Greater Grand Rapids Region of Leading Educators.

Firing up Fellow Teachers

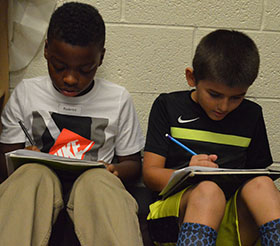

Teachers, now back in their classrooms – some with more than half the students just learning English – are applying what they are learning and communicating it to fellow teachers.

“(Leading Educators training) fueled that fire to come back and make a difference. I want to make what I’m doing better and not become comfortable and complacent, and to help my peers get that fire back,” said Kelly Compher, who is in her fifth year teaching second-grade at North Godwin Elementary, where about 90 percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunch and about 65 percent are English Language Learners (ELL).

A specific focus at North Godwin is looking deep into Common Core, the national academic standards, as a vehicle for improving equity, especially with ELL students.

Down the hall from Compher, fourth-grade teacher Jonathan Haga shared those sentiments.

“The whole process of what we have done this summer has really ignited a flame inside me about the learning every kid can do,” Haga said. “You get bogged down a lot by things we see and hear, test scores, all that stuff. But at the end of the day you have 26 kids in your classroom, and we can impact each one of them if we try hard and work hard.”

The Doug and Maria DeVos Foundation, is fully funding Leading Educators’ work in Grand Rapids, with educators signed on for a two-year commitment. Teachers attended an orientation session at the end of last year at the Grand Rapids-based regional institute, and spent five days in New Orleans at the National Institute in June. They will continue working together on Saturdays quarterly and with coaches in their districts.

Based in New Orleans, the program has been implemented in New Orleans and Baton Rouge schools, is also working in Washington D.C. and Aurora, Colorado, and is launching in Chicago and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Equity in the Classroom

A lot of thought needs to go into teaching equitably. Before lessons, Ginger VanderBeek, a fourth-grade teacher at Wyoming Public Schools’ Oriole Park Elementary, takes a minute to set learning goals. She uses an app called Class Dojo to randomly assign student partners, so everyone eventually works together.

VanderBeek makes conscious efforts to make sure all her students know the expectations and understand what’s being taught through pictures, by peppering Spanish vocabulary into her teaching and with other instructional practices she’s learned through Leading Educators.

In explaining the approach, she uses the term “scaffolding in” (which plays well with the fence illustration analogy.) To get students to understand lessons at the same level, measures are needed to support lower-performing readers, English-language learners, and any other student who may need a boost.

VanderBeek and her colleagues have set goals for the school that tie in with Leading Educators training. In three years they hope to bump up their M-STEP scores by an average of 10 percentage points per year. VanderBeek, as a teacher leader, will help train other teachers in collaborative groups called cycles of professional learning.

“The core of everything is equity,” VanderBeek said. “The most exciting thing is there is a renewed spirit of how to build in equity for all students. It feels like it’s given me something to grasp onto to close achievement gaps, and ultimately produce a learning environment with the right supports for all.”

Empowering Teachers is Key

Murphy said creating teacher leaders is a pivotal part of the program.

“We really believe in empowering teachers to lead professional learning from within the schools,” Murphy said. “That is one of the most successful and sustainable ways of closing the opportunity gap for students. Ultimately, we really believe in the ability of teachers to lead change, and we believe that is an area that hasn’t been tapped into in a really systematic way.”

At North Godwin, a school that has received accolades for achieving well above other schools with similar demographics, teachers see the need to step up as leaders.

“The reality is we’ve always known there is still more work to be done,” said instructional specialist Michelle Morrow. “We’re still not creating students who are ready for college and career, and I think that’s the case for many inner-city schools. The one-shot test might show a little bit, but being honest with ourselves we still feel we can do more for our students.”