Kimberly Reynolds has been navigating always-in-motion, ever-curious, pint-sized learners in her kindergarten classroom at Stoney Creek Elementary for 18 years. So she’s well versed in keeping her students on task for learning.

That was all too clear during a recent read-aloud, as her students valiantly maintained attention to her reading of “Never Take a Shark to the Dentist,” even as more than a dozen big people at the back of the room looked on.

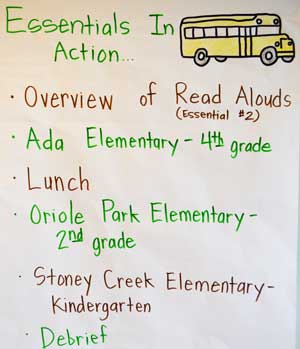

A quartet of literacy coaches from Kent ISD recently led a trio of early literacy essentials read-aloud field trips for teachers, administrators and other K-12 staff. Area public school districts that sent staff included Kenowa Hills, Grandville and Greenville.

On all three tour days, district staff visited the fourth-grade classroom of Bridget Bennett at Ada Elementary in Forest Hills; a second-grade class at Wyoming’s Oriole Park Elementary led by district literacy coach Brenna Dorgan; and Reynolds’ classroom in Comstock Park.

“Teachers want to see other teachers in action,” said literacy coach Sarah Shoemaker. “That’s how they learn best: They can ask questions and find out how others set it up, how they tweaked things to make it work for them.

“It’s really about collaboration, and taking away the barriers to making that happen.”

Each district could send up to five staff members, including one administrator, one literacy coach, specialist or teacher leader, and at least one classroom teacher.

“We wanted a team so that when the educators go back to their district, they have the support of the administrator and colleagues to continue the conversation and the learning,” Shoemaker said. “Learning in a group creates more opportunities for dialogue and accountability moving ideas into practice.”

Statewide Collaboration

About two years ago, the Michigan Department of Education, in collaboration with several partners including Reading Now Network, released a set of literacy essentials for kindergarten through third grade. Fourth- and fifth-grade essentials were released this year, and essentials for grades 6-12 will be released soon, Shoemaker said, adding that a set for birth through age 3 is being considered.

The purpose of the essentials is to focus Michigan educators and their practice on research-based instruction, Shoemaker said. It is seen as one of several moves toward achieving the “Top 10 in 10” goal the state Department of Education has established.

During the final session, with Kenowa Hills staff, Shoemaker shared that Michigan State University School of Education research found that K-3 teachers spend an average of 8.36 minutes a day doing fiction read-alouds, compared with 1.36 minutes of non-fiction text.

“In education — and life — after elementary school, most of the reading we require of students or job fields require of employees is non-fiction texts,” Shoemaker said. “What the research is clear about is that read-aloud is the single most important thing we could do for building the knowledge required for future success in reading. Read-alouds are beneficial for children of all ages and should occur multiple times throughout the day, as well as across content areas.”

In read-alouds, the teacher reads to students — whether from a picture book or science text — and uses visuals and tone, pace and volume, plus questions and comments and even references to previous work to encourage engagement.

Beyond traditional storytime, read-alouds include other subjects and are shown to build vocabulary, increase comprehension and students’ exposure to informational texts. For example, a read-aloud series on weather could include a picture book on clouds, precipitation and temperature.

Learning through Observation

In Reynolds’ kindergarten tour’s read-aloud — word of the day: never — she incorporated pictures that depicted the word and its opposite, always; question-and-answer time; “turn and talks,” such as never cross the street without looking both ways and always brush your teeth before bed; references to previous words of the week; time to get up and move arms and legs; and a few detours into the creepiness of centipedes and the tightness of teeth inside one boy’s mouth.

Afterward, the visiting educators debriefed by sharing their observations and asking questions of Reynolds based on what they observed.

“I was able to see firsthand the key components to read-alouds that can be adapted to my classroom,” said Shawn Herman, Kenowa Hills first-grade teacher. “It was encouraging to witness students engaging on a variety of levels with the read-alouds, and to understand how important it is to connect meaning with visuals for students to better understand vocabulary.”

Erica Philo, an interventionist/instructional coach at Zinser Elementary, said watching teachers and students interact in the read-aloud “made me think of other ways I could help teachers in this area.”

Tamara Gerig, first-grade teacher at Zinser Elementary, said she was encouraged to see how teachers on the tour wove read-alouds into the school day.

“It’s important to find that balance between learning new material and still finding the enjoyment in reading,” Philo said. “My students are continuing to learn how to read with expression, so that is one vital piece of what we work on.

“Another ‘aha’ moment was the importance of using video clips and pictures to help students work on instilling vocabulary into memory.”

CONNECT

For teachers: Three ways to fit read-alouds into your class day