It was time for Mary Galloway to highlight her skills during an interview for a nursing job.

“Can you handle the sight of blood?” asked interviewer Colin Brock, a West Middle School eighth-grader.

“Well, I got shot in the neck, so probably,” classmate Zoe Kincaid said confidently. She was role-playing Galloway, a Union soldier in the Civil War. “I think I am a strong woman because I had to lay in battle with a bullet in my neck for 36 hours.”

Hard to argue with that.

Rockstar Teachers Series: There’s just something about certain teachers that draws students to them in droves and keeps them checking in years, even decades later. Here, we highlight some of these rockstars of the classroom.

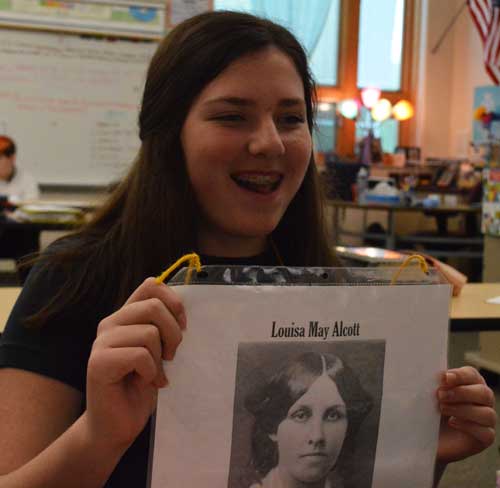

Colin jotted some notes. He would soon make a tough hiring decision, considering his candidate list included legendary women such as Harriet Tubman, Louisa May Alcott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and others who made their marks as nontraditional Civil War figures.

In the end, he offered the job to Clara Barton, a nurse who founded the Red Cross, played by classmate Tess Bainbridge. “She has a lot of experience with wounded people and a lot of hospital experience,” he said.

Eighth-grade history teacher Rebecca Debowski created “Women in the Civil War,” a lesson in which half the class play employers looking for workers during the war, and the other half play women interviewing for jobs. The goal is to teach the importance of women during the war, a lesson largely ignored during a time when men dominated political and military life, she said.

Debowski began by having students consider the “definition of true women in the 1850s,” also known as the Cult of Domesticity (possessing four cardinal virtues: piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness).

Following the job fair, students made a list of qualities they think go with “man” and “woman.” “The list for men included “leader,” “president,” “strong,” “masculine,” “non-emotional” and for women, “long hair,” “pink,” “dress,” “receptionist,” “nurse,” “mother” and “wife,” “cooking,” and “cleaning. Debowski said this pattern is common in the lesson.

After some discussion, current events such as the Women’s March and the Me Too movement come up, and students realize certain gender roles still exist. When that happens, students want to get out the eraser, she said.

“It’s like they realize what they did and they start going ‘feminist,’ ‘equality,’ They want to make the list better.”

Connecting the Dots

From women to slaves to the poor, in Debowski’s class, students learn history through perspectives not traditionally taught. Her style of teaching includes peeking into the lives of lesser-known individuals or marginalized groups who had an impact on or were affected by history’s biggest battles, wars and movements. She’s challenging students to wear different hats, walk in others’ shoes and glance through different lenses.

Depending on the lesson, students are cast as passionate abolitionists, unwavering activists, scrappy revolutionaries, representatives of the North and South, Union and Confederate soldiers, slaves, plantation owners and farmers. It’s all about making history go deeper and seeing how dots can be connected from way back then to now.

“There is something really powerful about experiencing history. We have this belief that history is all about dates and facts and dead men,” Debowski said. “I think there’s a way about bringing it to life, letting the kids experience, letting them act, that makes it more accessible and then allows them to make connections to today. It makes it more relevant, and then they can see those connections.”

‘Makes me want to dive deeper’

Students role-play during debates, adopting perspectives that aren’t their own and, for many, it’s easier to take a passionate stand while playing a character.

“They are able to be more vocal and contribute (to the debate), because it’s not their point of view. They are just giving that person’s point of view.”

Debating the Emancipation Proclamation as Union and Confederate soldiers has a way of sticking in your head, agreed eighth-grader Natalie Carey. “We do a lot of debates and they get really intense and heated. I think I remember better that way,” she said.

Added classmate Mackenzie Shride, “I like it because it helps us better understand what actually happened and, especially with this topic (“Women in the Civil War”), help women feel empowered. We do a lot of debates, which forces you to learn about each perspective.”

Another classmate, Cassie Wychers, said Debowski “really plans things that make it interactive for the students, and she loves history. She’s really knowledgeable. She’s so excited and enthusiastic about it, too… We talk a lot about minorities and the events that happened and how they were affected. It makes me want to dive deeper into what we’re learning.”

All About Interpretation

Debowski has taught at West Middle School for five years and, before that, for a year in rural Colorado. She completed her student-teaching in Liverpool, England. “That’s where I really became fascinated with perspectives, because having to teach the American Revolution from a British perspective was just so much fun,” she said. “It made me really realize that history is not just dates and facts. History is how you interpret those dates and facts.”

The Grand Rapids City High School graduate earned a bachelor’s degree in secondary education with a history major and English minor from Hope College, and a master’s in curriculum and instruction from Grand Valley State University.

She said she aims to write a couple new lessons each year, challenging students to consider different sides in events and issues.

For example, in “Patriot, Loyalist, Neutralist,” the class splits, with some students remaining in the middle, holding cards that indicate circumstances that would make them jump into the patriot or loyalist fold.

“As we go through various key events of the Revolutionary War, I let my patriots and loyalists debate each other,” she said.

At the start, students have only learned the patriot perspective, Debowski said. “They can really dive into ‘What were the loyalists’ reasons for staying?’ and ‘What were the reasons people didn’t want to get involved in the war?’”

Another lesson focuses on Sherman’s March. Students play various people involved in the 1864 march through Georgia, and learn about perspectives on Major General Sherman as hero or villain. Another lesson, “The Trial of Henry Wirz,” puts students in a mock trial of the only Confederate soldier charged with war crimes. The highly controversial case often leads to talk about current events, including whether confederate monuments should be removed from public spaces.

History is Messy

Debowski also adapts lessons by teacher Bill Bigelow, including “The Unconventional Constitutional Convention,” in which students work in groups: upper-class merchants, bankers, lawyers, plantation owners, enslaved African-Americans, Native Americans, working-class people and women. “All have different things they want to accomplish written in the Constitution… they try to build alliances with each other and say, “I’ll vote for this if you vote for that.”

Students send representatives from each group to the Constitutional Convention, where the U.S. Constitution was created in 1787. They debate and write their own classroom Constitution, and their sense of social justice tends to emerge, Debrowski said.

“It’s so funny because they free the slaves; women get the right to vote; they allow payments in kind for the farmers.”

“Then we compare that to the real Constitution and the kids realize, ‘Wait a minute, this Constitution really was only benefiting wealthy, white men… We have a really tough conversation in class that this is our founding document, and it was supposed to be a government of the people, for the people, by the people, and yet 98 percent of the population is not included.”

She comes around to that fact often.

“Every time we look at a major document or major moment, I always bring people who weren’t at the table into the conversations.”

Debowski’s teaching naturally leads to history’s many parallels to current events, and students learn movements are always more nuanced than a textbook makes them seem.

“We have to understand that this country is complicated, and our history is messy, and there have just been times we haven’t quite lived up to that (principle), “All men are created equal,” Debowski said.

Civil Discussions

Many lessons raise the question of what disparities and inequalities still exist today, she said, which leads to interesting discussion and varying opinions. She encourages push-back and respectful disagreement, while modeling appropriate civil discourse.

“I always say it’s so important to hear the other side because it helps you develop your own so much better.”

She also teaches students to share their own experiences, which builds empathy. “We can’t argue with experiences. We can argue with political ideologies, but personal experiences are personal and very real and something that should be shared,” she sad.

Her overarching goal, she said, is to teach that American ideals are worth striving for. “The fact that this country was founded on that belief — All men are created equal — means we are in constant pursuit of it… Even if we haven’t gotten there yet, America will always be America if we are striving toward that kind of Utopian society.”

Debowski said she witnesses and guides her students as they learn to look at things in a more nuanced way and respect what one another have to say, from every perspective.

“They know we are living in a country where dialogue is not happening and criticizing is happening and pointing fingers is happening. They might not know the issues, but they know the tension is there.

“I’m so proud my kids can have conversations so much more maturely than adults. That took a lot of modeling and teaching them how to do it, but once they had the tools to do it, they are so good at it.

“I keep telling them, I’m just a measly middle school teacher, but you’re going to change the world and I’ll get to watch it.”

CONNECT

Students Go Greek Questioning Discussing Issues Like Socrates Did

Students On metoo Movement: ‘It Kind of Scares Me’