Aunner Calderon took a break from filling out a college scholarship application to recall his freshman year in the Union High School Newcomers program, when he was indeed a newcomer from Guatemala.

“When I moved to the United States I didn’t know how to speak English, and I didn’t have the confidence to speak the little English that I knew,” Aunner said.

But with the help of his teachers at Newcomers, a program for newly arrived immigrant and refugee students, he mastered English well enough to move into regular classrooms in four weeks — a process that normally takes Newcomers students a year.

The senior credits those teachers for launching and sustaining his high school success: compiling a 4.2 GPA, earning 48 early college credits, and now applying to half a dozen Michigan universities, including the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. Being part of Newcomers has been key to his good experience of school, said Aunner, who wants to become a surgical physician’s assistant.

“More than students or classmates, we become like a little family,” he said in impeccable English. “We help each other, we practice the English we are learning. I feel that is something that really helped me.”

However, the number of students being helped like Aunner is down drastically this fall, following the Trump administration’s ban on immigrants from seven countries and sharp reductions in refugees allowed into the country. The Oct. 3 student count day recorded 20 students in Newcomers, down by 65 from projections and by 120 from last spring. As a result, three of the four Newcomers teachers are being transferred to other GRPS schools.

“It’s sad, because (students) have less opportunity,” said Amanda Bursey, a teacher who will continue in the program. “A lot of them came here because they were escaping some terrible situation. That’s not an option for so many kids now. What about those other 120 kids that could have been here, is what we think about.”

Federal Restrictions Impact Arrivals

Newcomers serves students from ages 14 to 19 who need to learn English, math and other basic skills, and many of whom lack formal education or school documentation. Often, their families have come from refugee camps or fled traumatic situations in their home countries.

Since its inception seven years ago, Newcomers has normally seen between 60 and 90 students per year, said Halima Ismail, a school improvement facilitator who oversees the program. Last year saw a jump to as many as 162 at one point, boosted by an increase in refugees admitted under the Obama administration in 2016.

Ismail attributes the drop this fall to the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants at the Mexican border; its ban on refugees from seven countries including Muslim majority countries such as Iran, Syria and Somalia; and its slashing of the U.S. refugee limit.

“They are not allowed to come across,” Ismail said of many students seeking entry into the U.S. “They’re stuck in all the red tape.”

After a substantial increase in refugees coming into West Michigan two years ago, to almost 1,000, the area saw “drastic cuts” in the numbers to less than 600 arrivals in 2017 and this year, said Susan Kragt, executive director of the Refugee Education Center.

Other GRPS schools are also taking an enrollment hit due to the federal actions, and likely due to higher housing costs as well, said spokesman John Helmholdt. Tentative total enrollment figures show a decrease of 125 students from last year, to 16,568.

“Right now the national dialogue and the policy making that’s occurring is creating a hostile environment toward immigrants and refugees,” Helmholdt said. “It’s really sad and disappointing that children that need and deserve a high-quality education are effectively being denied that opportunity.”

By the Numbers

Bethany Christian Services, based in Grand Rapids, had 187 individuals, of all ages, arriving through its refugee resettlement program in 2018. That’s down from 276 in 2017 and 366 in 2016. “The drop is primarily due to the decrease in arrivals coming to the U.S.,” said Kristine Van Noord, program manager for refugee adult and family programs.

“We are still getting people, but not near at the numbers we were in 2016.”

While the Trump Administration capped the number of refugees allowed to enter the country at 45,000 in 2018, only 22,491 have entered. That trend is similar at the local level. At Bethany, its 2018 per-agency capacity for new arrivals was 267, but only 187 have arrived. Samaritas, which offers resettlement services in Grand Rapids, had a capacity for 230 individuals, but just 138 have come. (For 2019 the national capacity of refugees to be allowed in the country, set by the Trump Administration, is even lower, at 30,000.)

Multiple factors are keeping numbers of new refugee below capacity including increased security screening steps and delayed overseas processing.

Many refugees who are arriving are from Congo, and are choosing Grand Rapids as their destination because of the large community of Congolese that has settled in the area.

‘They want to learn. To them it’s this beautiful opportunity to even come to school.’ – teacher Amanda Bursey

Bethany Christian Services considers multiple factors when housing refugees: size of families, availability of safe and affordable housing and proximity to friends, extended family or community members. Most Congolese are settling in Grand Rapids because they tend to have large families and the city has larger houses available than other areas, Van Noord said. Burmese and Bhutanese families have settled in the Kentwood area in previous years.

Increased housing costs have led to fewer options in both the city and Greater Grand Rapids areas.

Surrounding districts have not seen a significant decline in Newcomer and immigrant students, according to information from Kentwood, Wyoming, Godfrey-Lee and Godwin Heights districts. While reasons are unclear, it could be due to secondary migration patterns as people move closer to community members or other resources, Van Noord said.

Learning the Basics, Getting Support

For those students who do attend Union’s Newcomers program, it can play a crucial role in their entry into the U.S. school system and culture. Typically they spend their freshman year in the program, augmented by additional study after school and during the summer. Some continue to receive help after they enter regular classes.

“We give them one year to give them a fighting chance, because they have had no support in the language,” Ismail said. “We have to at least give them a basis of some literacy skills.”

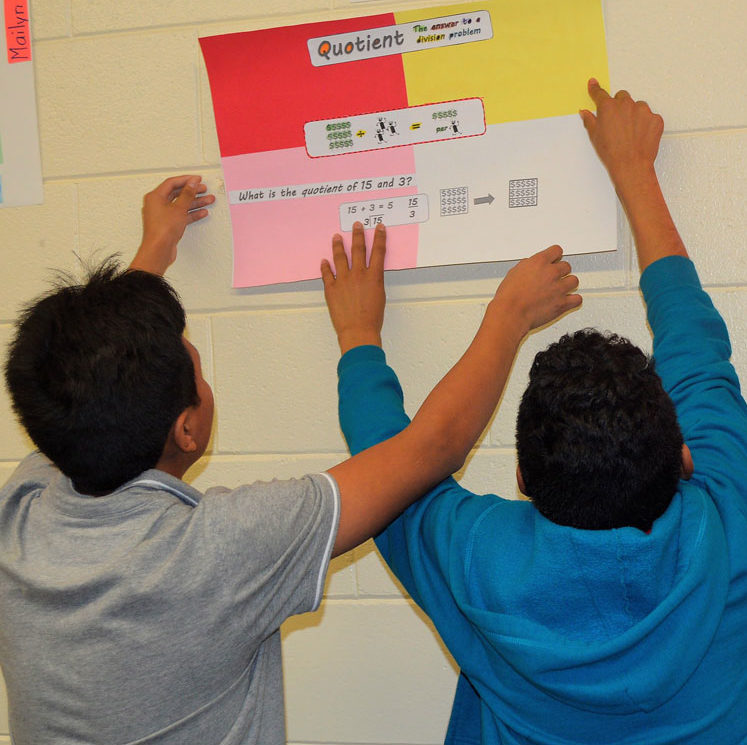

Amanda Bursey incorporates literacy skills into all her classes, including math. On a recent afternoon, she asked one of her 10 students, “What did you eat for dinner yesterday?” When he hesitated, his desk mate answered, “Hamburger.”

Each student took out a sheet organized by days, with new math words for each day. Yesterday’s words were “unit of measurement,” which Bursey reviewed.

“If I asked you, Hector, how many hours in one day, you would say …” she asked one student. “Twenty-four,” he answered. “Twenty-four what?” she said. “Hours,” he replied. “The unit is hours,” not feet or boxes, she stressed.

Schooling students in “all the basic math words,” like equal and multiply, is essential if they’re going to solve equations, Bursey said later. It’s a task she gladly takes on, finding most of her students to be highly motivated.

“They want to learn,” said Bursey, a veteran ESL teacher. “Every little thing is new for them, so they’re excited to learn it. They’re in a new country. To them it’s this beautiful opportunity to even come to school. They get all these opportunities that maybe they didn’t have in their country.”

Aunner Calderon appreciates the opportunities Newcomers has given him since moving to Grand Rapids with his mother and little brother. It allowed him to form good relationships with teachers, who continued to help him after he left the program, and set him on a path of volunteer work at places like Kids’ Food Basket. He said he feels bad that fewer students are able to take advantage of the program.

“We understand that students from different countries come because they did not have a really good life in their home countries,” Aunner said. “For me, it is devastating to see that there are not things that are helping those students.

“The United States offers one of the best qualities (of) education. I believe that everyone should be able to have that.”

CONNECT

Study reveals economic impact of refugees and immigrants on Kent County