More than 50 students huddled at one end of the classroom, squatting and packed together on the floor. Moments earlier they had all poured in here, across the hall from the cafeteria, where they’d been gabbing over lunch.

Then came word over the intercom: This is a lockdown drill. In less than a minute, about 200 students emptied out of the lunch room and ducked into nearby classrooms, the choir room, the kitchen – anywhere out of the line of fire.

Shortly after 11 on a Thursday morning, students at the Rockford Freshman Center were rehearsing a nightmare: an active shooter in their school.

“I need you to be absolutely silent now,” substitute teacher Megan Normington told the students huddled in room 141. “Absolutely silent.”

For the most part, they were, aside from some whispering, a cough, and a few boys giggling after one of them burped. A few girls nervously tried on each other’s glasses. These are freshmen, after all, and they’ve been doing these drills since kindergarten. They’re routine, as common as tornado drills.

Still, these students know that, like a tornado, this nightmare could really happen.

“It used to bother me when we did these,” admitted Alexis Tamminga, a slender blonde in a sky-blue tie-dyed shirt. “I thought it wasn’t really necessary.”

Her thinking changed after talking to her dad about school shootings, and watching TV coverage with him of the Parkland, Florida, killings. Seeing its searing images of weeping parents, she thought of hers, and other Rockford moms and dads.

“It made me think, ‘What if that were to happen at my school?’” Alexis said. “Those parents, they all looked so sad.”

| Drill compliance uneven around state, country

In Kent County, Kent ISD and the Kent County Sheriff’s Department have an online reporting system to ensure districts are complying with state requirements. All districts are required to post their drills on their websites, said Mark Larson, coordinator of safety and security planning for Kent ISD, adding he is “confident of compliance.” However, statewide some districts “have not done the required drills and have not posted them on their website which is required and recommended,” said Larry Johnson, past president and current vice president of the National Association of School Safety and Law Enforcement Officials, and a member of the Michigan School Safety Task Force. Around the country, some districts “still struggle with doing these drills on a regular basis,” added Johnson, executive director of public safety and school security for Grand Rapids Public Schools. “This occurs for various reasons and we do not understand why this does not stay on the radar of school administrators.” He noted there is confusion or lack of knowledge about newer lockdown models, such as “run, hide, fight” and “avoid, deny, defend,” adding, “The key is to have individual communities work together to come up with a model than is acceptable to them” and implement proper training. Parents should also be informed promptly of the drills and understand how they’re conducted, to avoid “unnecessary trauma” for younger students, he said. Despite the difficulties posed by different levels of security among districts, he added, “the good thing about all of this is districts are thinking about lockdown and conducting the drills.” |

Building Muscle Memory

Sad but necessary: That’s the common view of the lockdown drills that are part of normal school life for today’s students. In Michigan, schools have been required to hold at least two such drills per year since the measure was signed into law in 2006.

‘It made me think, What if that were to happen at my school? Those parents, they all looked so sad.’ – Alexis Tamminga, freshman

The Freshman Center drill was one of four lockdowns they’ll conduct this year, for different situations: students at lunch, in class, and in the halls between classes. Students know ahead of time that they’re coming and are told what to do before they happen.

“The objective is to save lives,” said Principal Tom Hosford. “We don’t want our students to be scared, but we do have a lot of dialogue about being ready.”

In this case, being ready meant getting to the nearest room where a door could be locked – fast – then huddling out of range of a shooter outside the door. By rehearsing the various scenarios, officials hope students will acquire the muscle memory to know what to do in case of the real thing.

“You never know how you’re going to respond to a critical incident like that,” said Scott Beckman, director of security for Rockford Public Schools. “By doing these repetitively, having kids go through the drills, you want them to respond to how they’ve been trained, because it will take over during a critical incident rather than them having to think their way through it.

“I don’t want kids to be paranoid and go through life fearful,” he added. “But I also want them to understand there are things out there that are unpredictable and we need to respond in an appropriate way.”

Training for Different Scenarios

The appropriate response depends on the situation and the proximity of the threat. For instance, if there is an active shooter in the building, a student may want to take a nearby exit outdoors; or, if trapped in a classroom, grab the best available weapon, like a chair or coffee mug, Beckman said. “What we don’t want is people freezing,” unable to move because of panic, he added.

Students are also drilled on “shelter in place” scenarios, prompted by incidents such as a chemical spill near the school, where classroom doors are locked but teaching goes on. That’s in addition to fire and tornado drills, and, in Rockford by choice, a medical emergency drill.

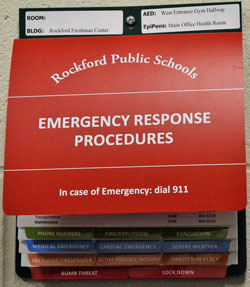

At the Freshman Center, teachers and staff are trained in drill procedures, and each classroom has a booklet detailing them. For principals like Hosford, the possibility of a shooting is never far from their consciousness. It can be triggered by the sight of a suspicious parked car, or a visitor wearing weather-inappropriate clothing.

“We’ve been hardened because of the all the situations that have happened,” Hosford said. “Every building administrator thinks about student safety every day, all day long – even in my dreams.”

For Assistant Principal Kelly Amshey, that constant awareness of risk extends to her three children in the Rockford system.

“I always think about, how does the kindergarten teacher relay this to my baby, in a way that doesn’t make them scared to come to school?” Amshey said.

Move Quickly and Be Quiet

On the day of the recent lockdown drill, students were briefed over the PA that morning on what to do when it happened. Hosford and Amshey were poised to observe whether students followed the instructions. So were two members of the Plainfield Township Fire Department.

About 200 of the school’s roughly 700 students were eating lunch when the drill was announced. They poured out of the cafeteria’s double doors and headed to the nearest open rooms. All classroom doors are kept locked but are sometimes left propped open.

‘That’s their everyday life now. They don’t know a world where there hasn’t been a school shooting.’ – Freshman Center Principal Tom Hosford

Normington, the substitute teacher, stood by her door and waved students inside. She herded them into one end of the room: “I need you guys to squish as far as you can behind the teacher’s desk.”

Then, on her order, the room went eerily silent, as did the whole school.

Hosford, Amshey and other staff walked the halls to make sure everyone was inside, doors locked, lights off, students out of the line of sight. After three minutes and 45 seconds, a chime over the PA signaled the drill was over. Normington’s students rose hastily, yakking and laughing as teenagers will.

Feeling More Prepared

A handful stayed behind to reflect on the experience. They said the drill didn’t cause them anxiety, but did conjure thoughts of “the real deal.”

“It makes me feel kind of prepared, and kind of like emotionally prepared too, if anything were to actually happen,” said Ashley Hillis. Still, she wondered, “if it was real, what would (students) actually be like?”

Jack Adams likened it to a tornado drill, insisting there was no way to be prepared emotionally for a shooting.

“There’s a huge difference between a drill and the real deal,” he said. “I feel like kids treat those two very differently.”

But they all agreed the drills are worthwhile. Said John Pekrul, “You definitely have a better idea of where you want to go, especially in a situation where you’re at lunch and not in a locked classroom.”

Normington, the sub, was sobered by the drill, knowing they would have barricaded the door in a real situation.

“It hurts, it hurts a lot,” she said. “It’s really sad we have to practice it. But I guess it’s necessary now.”

Hosford said the drill went well, though in a real incident students would have had to move a lot faster, he said. “They went to the right spots, which is what we want.”

As for his students’ calm reaction, he said it’s a sign of how frequently school shootings happen. “That’s their everyday life now,” he said. “They don’t know a world where there hasn’t been a school shooting.”

For all of Rockford’s pride in its schools and community, Amshey said she knows all schools are always at risk. She was reminded of that when hearing a talk this summer by Frank DeAngelis, the former principal of Columbine High School, site of the infamous 1999 massacre. DeAngelis said he would never have believed such a thing could happen at his school.

“I don’t think anybody thinks it couldn’t happen here, but it’s beyond belief that it could,” Amshey said. “I hope it always stays beyond belief that it could.”

CONNECT

Scarred by school shootings: effects on survivors since Columbine