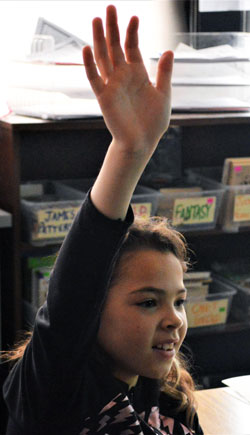

Prompted by teacher Alex Kuiper, Godfrey Elementary School third-graders identified the base word of “sweetness.”

“Sweet,” they said in unison.

“Did we have to change the word at all?” Kuiper asked, about adding its suffix.

“No,” they answered.

| The cut score

According to MDE guidelines, third-graders whose scores on the ELA portion of the M-STEP are:

The law requires that students flagged for retention:

“Good cause” exemptions may be made if a child:

|

Changing “happy” to “happiness” does require a change, explained student Horlando Mattias moments later. “You have to take the ‘y’ out, put in an ‘i’ and then add the ‘ness.’

Michigan educators and students are facing a new reality as they focus on reading, writing and spelling every day in classrooms like Kuiper’s. Third-graders whose results fall below a newly announced “cut score” on the ELA portion of the M-STEP exam may not pass on to fourth grade when a law takes effect beginning in the 2020-2021 school year.

The law, referred to as “Read by Grade Three,” or RBG3, was approved in 2016, requiring students who are more than one year behind grade-level in reading to repeat third grade and receive additional support.

The cut score of 1252 or lower means far fewer students will face retention than are identified as below grade level in reading on the M-STEP. (Students are scored as Proficient, Partially Proficient and Not Proficient. The Not Proficient range is 1203 to 1279. On last year’s test, 31 percent of students scored as Not Proficient category and 24.6 percent as Partially Proficient.)

To establish the cut score, state officials worked with educators and technical experts over six months last year.

“A performance level of “not proficient” on the ELA test does not necessarily tell us if the student is a grade level behind in terms of their reading,” wrote MDE Deputy Superintendent Venessa Keesler in a memo. “To comply with the RBG3 law, a unique and separate cut score for the third grade ELA test was established specifically to measure reading as outlined in the law.”

Still, according to information from the Michigan Department of Education, about 5 percent, according to 2018 data, of Michigan third-graders would face retention under the new benchmark. That’s about 5,100 students. Those with scores from 1253 to 1271 — 17.5 percent of students — would be recommended but not required to receive extra reading support

Those with scores 1272 and higher– about 77.5 percent of students –would meet the grade three reading requirement.

Kelli Campbell, Kent ISD director of teaching and learning, said she is glad to see more than three-quarters of students meeting the reading requirement, but is curious if there will be variations from year to year.

“I’m patiently waiting to see what this year’s data looks like,” she said. “Understanding that the cut score goes into effect next year, before I jump to any conclusions I’d like to see at least two years of data.”

She’s also interested in district-specific data, and the impact on sub-groups (students categorized by demographics including socio-economic status and ethnicity). “How does it impact them and how do we best meet their needs?”

The Possible Impact

Godfrey-Lee Public Schools Superintendent Kevin Polston said the law will disproportionately impact students of color.

According to the third-grade test scores of this year’s Godfrey Elementary fourth-graders, seven of 114 would have met criteria for retention, Polston said. “All were economically disadvantaged, six were students of color, two were English learners and two were homeless,” he said. “This bill is going to further marginalize an already marginalized community.”

About 95 percent of Godfrey-Lee Public Schools students are economically disadvantaged, and 78 percent are Hispanic. “My take is if we do follow through with (retaining) those seven kids, that’s seven too many that are subject to a bad law,” Polston said.

Polston pointed to a long-term statistical study in Florida of 1,500 third graders retained for failure to meet Florida’s retention policy and 1500 promoted third-graders who also failed to meet the benchmark but were promoted to fourth grade through a “good cause exemption.” While retained students did better than those promoted in fourth and sixth grades, by 10th grade there was no significant difference.

“Why are we trying to do something so some can feel good about accountability when the research on retention is clear? It doesn’t work,” Polston said. “The research says if we put supports and interventions in place for these students then that will work.”

Polston said the law seems like an effort by the state to test the progress of a school or system, not to help students. “They are trying to tie it to an individual’s progress,” he said. “There are much better ways to do that. Kids don’t all start the race from the same place… If (the law is) really to measure progress of a student, then we’ve got to do better than that.”

Several “good cause” exemptions allow students who meet retention criteria to be promoted, including the opportunity for parents to excuse their child from retention. Others include if a child has an Individualized Education Program (IEP) plan for special needs or is an English language learner. How districts utilize exemptions is crucial, Campbell said. Ann Arbor Public Schools, for example has said it won’t retain students based on reading ability, instead opting to grant exemptions.

“My issue is, why do we need exemptions for a bad practice?” asked Polston. “The practice is bad. You shouldn’t duct tape it together with these exemptions. You should get rid of the bad practice.”

Godfrey Elementary School Principal Andrew Steketee said there’s a lot more to consider than a test score in determining if a student needs to repeat a grade.

“You have to be aware of each individual situation, their homelife, whether there’s trauma in the student’s life, how long they’ve been in the United States,” he said. “If you just go by test scores you aren’t looking at the individual needs of the students.”

Increased resources and individual student plans are positives of the law, said both Polston and Campbell.

“The key parts of the law are research-based best practice,” Campbell said. “We should know where students are at, reading-wise — each one of our kids. If they aren’t performing we need to dig deeper and figure out why.”

She continued: ‘If a kid’s not reading, there needs to be an intentional plan around how we are going to help this kid get to grade level.”

CONNECT

Will Michigan 3rd Grade Reading Law Hurt Poor? Florida’s History Says Yes