Fifth grader Elsa VanDeven gave the object she had “unearthed” from a simulated archaeological site on the floor of her classroom a long, determined look and turned it over in her hand.

“Is this a hand iron?” she asked teacher Linda Sawade. “Pinching tongs? Snippers used to cut candle wax? A curling pipe?”

Said Sawade: “Read the article in front of you. Remember, the things you find are clues about who lived there and what they did.”

An advertisement in a copy of a newspaper clipping from Jamestown, Virginia, site of the first English Colonial settlement, revealed the item’s identity: a curling wand used on men’s wigs.

Discoveries were being made all around Elsa. Classmates who worked in their own assigned areas along the dig site exclaimed “Arrowhead!” “Are these nails?” and “Does anyone have a cross-mend for this?”

American History Unit

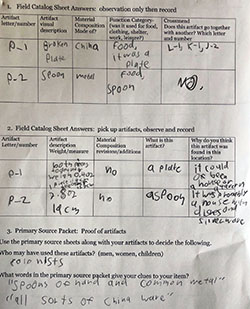

It was the second year Sawade led the dig simulation, where students made like archaeologists to discover not only how they work at an excavation site, but how they discover that history is under our feet every day.

Sawade spent a week a couple summers ago at the Colonial Williamsburg Teacher Institute, thanks to a grant from the EGR Schools Foundation. She modified a lesson she learned while there, and brought back several primary documents such as newspapers, journals, photographs and advertisements.

For about two weeks leading up to the excavation simulation, her students watched videos about Williamsburg and nearby Jamestown, worked with gadgets from more recent history that aren’t common today, such as a nutmeg grinder from the 1800s, a potato chipper from England, a metal milk bottle opener and an egg separator — to learn how to use primary documents to figure out found objects.

“One of our goals is to study colonization and settlement using primary resources, and focus on the convergence of enslaved peoples with settlers,” Sawade said. “The whole thing is that we understand who was here already and how it changed over time.”

History Happening Now

Using a tarp Sawade “borrowed” from her husband as an excavation grid, she laid out artifacts much like those found at actual settlement dig sites. The artifacts she uses are reproductions and antique store finds, she explained.

“I just think it’s a great way to learn history. It sure makes it more interesting when they know these things are really being dug up.”

As in, dug up right now. For example, she said, news outlets in Northern Michigan are reporting digs at Fort Michilimackinac with finds from the same period her students are studying. Those same students take trips to Mackinac Island in fourth grade, and will visit Greenfield Village in May.

“I like to show them how history is taking place all over,” Sawade said. “You want them to be engaged, and you want them to love history as much as you do.”

CONNECT