Forest Hills — David Simpson got the phone call from Superintendent Dan Behm at 2:03 p.m. on Oct. 19, seven minutes before students were dismissed for the day. Under the recommendation of the Kent County Health Department, the building was closing temporarily to slow the spread of coronavirus. Students would be learning from home at least through the end of the week.

Simpson, principal at Northern Hills Middle School, knew it might be coming. Nearly 25% of his eighth-graders already were quarantined, and Northern High School had closed the day before.

The first thing he did, he recalled, was make an announcement to teachers to look for an important email from him very soon. There were speakers outside, and he wanted students to learn from their parents once they were home.

Then he composed a message to families. Wednesday was already scheduled to be a half-day. He told them the news, and that students would receive a less-than usual amount of work for one day. “I asked them to just give us 24 hours,” Simpson recalled.

In her science classroom, Terri Dufendach had supplies set out for a hands-on water cycle lab experiment to introduce seventh-graders to the unit on weather. “When I heard we had to close, I did not embrace it at all,” she said. “I just thought ‘shoot, shoot, shoot.’ But we pushed Plan A to the side and started on Plan B.”

Eighth-grade math teacher Tonja Bogema was preparing to give a test the following day on linear and nonlinear equations. “My first reaction was ‘How on earth are we going to do this?” she recalled. “I’ve never given a test online because so much of it is showing their work.”

Said Simpson, “I think this pandemic has really shown that you can plan for something, but life isn’t always going to go from A to B to C; there are going to be some zig-zags.”

Synchronous Learning

During the building closure from Oct. 20 to Oct. 30, administrators and staff still reported to work. Teachers led their classes from their rooms while students followed along from home.

“Thankfully, the kids know how to learn remotely now. They knew how to communicate with us from home, and we had in-person relationships with them, which was huge,” said Dufendach, who is in her 39th year of teaching and insists she’s “having too much fun” to retire.

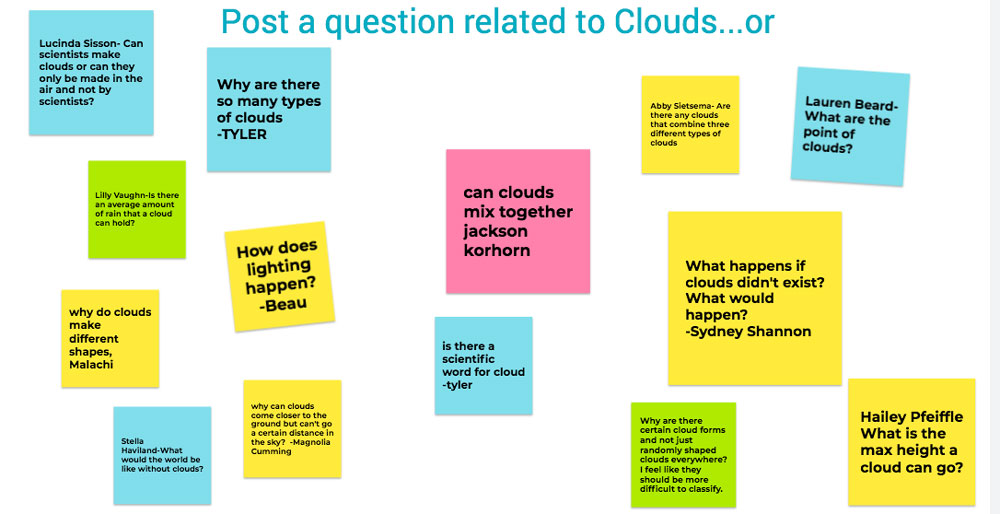

“I pushed the labs to the side, but … they’re Zooming, Jamboard-ing, Kahoot-ing, Flipgrid-ing… they are science-ing; they really are, and they’re questioning and sharing. The kids have been rock stars.”

“Right now, this afternoon, they are creating a video over weather and climate topics, which we are going to address the next few weeks,” Dufendach said.

For her math students, Bogema made three short videos for them to watch that first day at home, and held a drop-in Zoom help session in the afternoon.

“I’m very proud of our team and the work they pulled off in 24 hours. No one signed up to become a teacher to do what we are doing now. There’s no class for this.”

— Forest Hills Middle School Principal David Simpson

She and teaching partner Rebecca Beltman then got to work putting the paper test into a Google-friendly format that was less than friendly for them to create.

“It took seven or eight hours to make it,” Bogema said. “You can’t just put a square root symbol, for example. It’s a lot of logistics. For our curriculum, it’s all collaborative, investigative. It’s not curriculum that translates readily to online.”

Once the test was created, the pair had to figure out how to make sure it could be taken in the allotted time, the process to ask questions and how to discourage the temptation to look up answers. “It actually worked out way better than I thought it would. But I didn’t get a whole lot of sleep Wednesday night.”

Human Connection

Though students could see and sometimes talk with one another on their computer screens, Dufendach said she could see they missed interacting in person. “That’s what middle school is all about.”

For her, being at school with no students: “It’s too quiet. Maybe the first day we all went ‘yay.’ But now? Middle school is never quiet.”

Bogema agreed. “I’d rather have kids here,” she said. “We’re making the best of it, but I feed off their energy.”

Said Simpson, “Our kids are social creatures. We really saw in the spring the impact of lack of socialization on their mental health.”

One plus of going virtual: “This was the first time our teachers and our kids were able to see each other without masks on,” he said. “That human connection came from having to be virtual.”

Praise All Around

Ask any middle-schooler what they want more of and they’ll probably say freedom, Simpson said. “But the reality is, they thrive with structure and consistency.”

As part of the remote learning plan, Northern Hills teachers took attendance at the start of every hour. Independent and group work time, one-on-one video guidance, and open office hours were set so students knew what was expected of them.

“I’m very proud of our team and the work they pulled off in 24 hours,” Simpson said. “No one signed up to become a teacher to do what we are doing now. There’s no class for this.”

As for the students, “One thing we found was, kids didn’t necessarily need help but they were signing on just to connect,” Simpson said. “And we’ve had better attendance with this virtual setting than we do on a normal day (in person).”

Bogema said this is her 22nd year teaching “and the hardest I have ever worked in my entire life. We’re staying flexible. I was a gymnast growing up, but this is ridiculous.”

And the in-this-together spirit that surfaced in the early days of the pandemic — Northern Hills Middle still has it.

Bogema praised Simpson for “the level of trust he puts in (teachers) and the space he gives us to get our jobs done,” her son, a sophomore at Eastern High, whose hybrid learning “gave me the parent perspective to just give students more grace,” as well as fellow teacher Amy Sprik — “She’s just really good at Google.

“Leaning on our colleagues’ expertise has been so helpful. Not every school has that,” Bogema said. “The culture at our school is amazing.”