All Districts — Of all the steps that must be taken when electing a new U.S. president, the process of confirming each state’s Electoral College votes is often overlooked. The law requires Congress to take the final step of reviewing and certifying the electors’ votes, but since Electoral College results cannot be overturned, this action rarely makes the news.

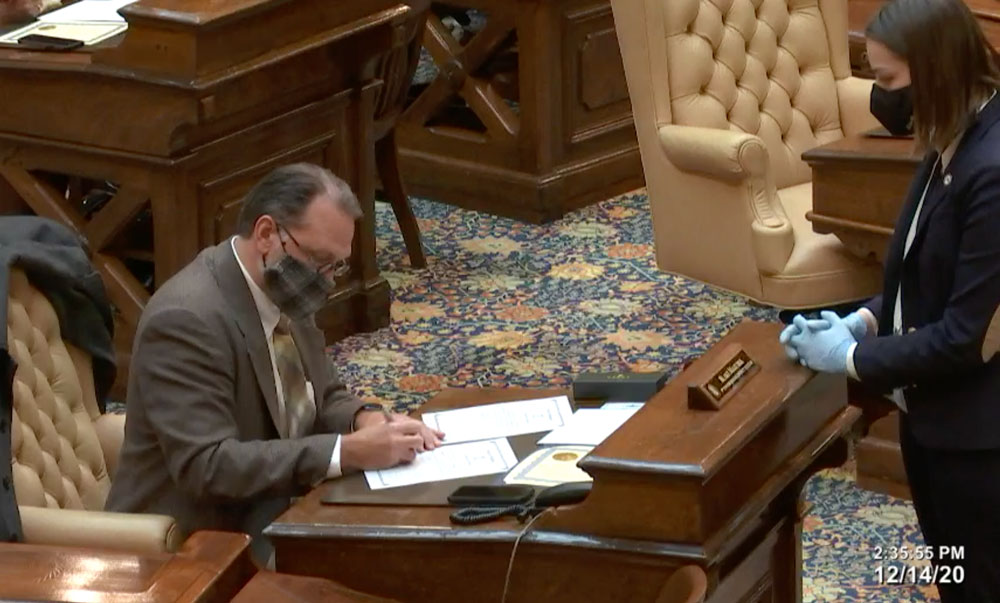

Grandville Middle School’s U.S. History teacher Blake Mazurek had a particularly vested interest in watching this year’s count, however. As one of Michigan’s 16 electors for 2020, his signature was in one of the mahogany boxes in the Senate chamber, and it would be counted toward the final confirmation of Joe Biden as the next president.

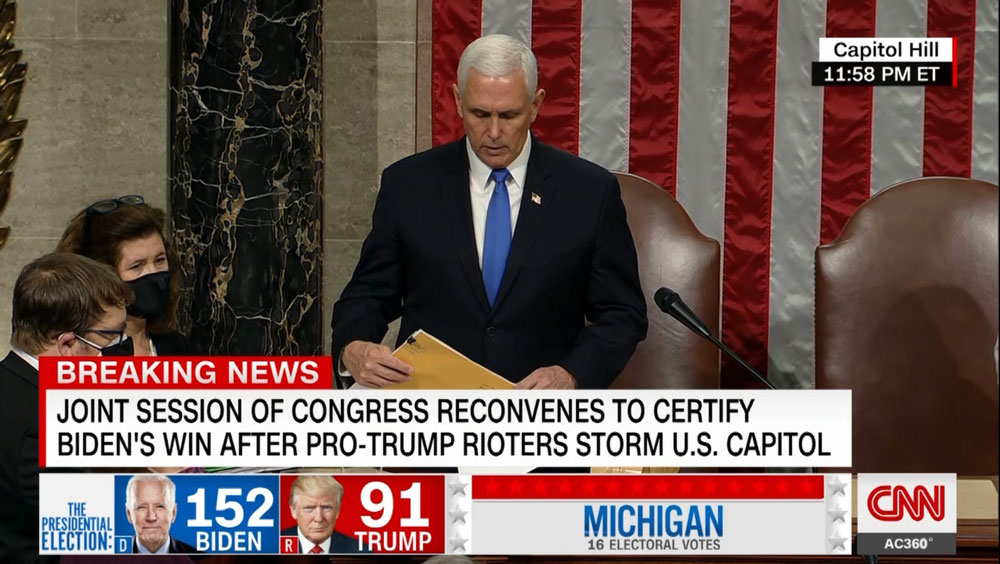

But just minutes into Wednesday’s joint session of the House and Senate, led by Vice President Mike Pence, the day turned violent. The vote count was interrupted live on TV as an angry mob overtook security and broke into the U.S. Capitol. Spurred on by President Trump’s baseless claims of election fraud and his refusal to accept Electoral College results, rioters broke windows and doors inside and looted offices while elected officials evacuated and sheltered in place.

While Congress later reconvened and worked into the night to confirm Biden’s election victory, Mazurek knew the news would be hard for students, parents and other teachers to digest. In his nearly 30 years of teaching, he has walked students through other tragedies including 9/11, the Oklahoma City bombing and several school shootings.

A day after the attempted coup, Mazurek sat down with School News Network to discuss Wednesday’s events as both an elector and historian, and how teachers and parents can help children navigate trauma and uncertainty in the wake of such events. An abridged version of that conversation follows.

SCHOOL NEWS NETWORK: As an elector for Michigan, what were your thoughts yesterday as you saw the rioting unfold?

MAZUREK: I anticipated a long day, because we had been hearing reports about the senators that were going to object to the (election) results in some states. I didn’t anticipate that we would have our Capitol attacked and overrun. I mean, the word “insurrection” is being used by members of the Senate. And to think that we’ve had presidential elections in the midst of civil war and still had peaceful transitions, what happened yesterday is very troubling. It’s a bad sign about the health of our nation right now.

We have some issues in this country that we have got to look at, like how we handle a situation where the president’s rhetoric pushes people to behave in manners that are not the norm. It should terrify the American public.

SNN: Did it feel more impactful knowing that your name and signature was on a certificate inside that chamber, and that the rioters wanted to discredit the votes of your fellow electors?

MAZUREK: Well, of course it had an extra layer for me because of that personal connection. I was eagerly history-geeking, waiting for them to get to Michigan. But then suddenly, I see commotion on the split screen (on TV) with chaos outside, and the Secret Service came in and whisked away our vice president. My heart just sank, because I feared for his safety and for every person in that chamber’s safety, and I worried about the police that were trying to stop this thing.

But one of the things that popped into my head at the same time was, Did somebody grab those ballots? Because my name was inside one of those boxes. I’m sure 99% of people were not thinking of that. (Editor’s note: Congressional staffers were able to safely remove and secure all documents.)

SNN: You’ve been open with your students about your role as an elector. What are you telling them today? How are you approaching the discussion?

MAZUREK: I devoted the entire hour of class to just answering questions and talking through it. I shared some of my personal feelings of what I felt while watching what happened, and I just talked to them as a human being, as a fellow citizen and as their teacher.

Over the course of my career, I’ve had the “morning after” lessons with kids far too many times. Every human has an emotional response to tragedy — kids, teachers, administrators, parents, everybody. And I firmly believe you have to be real with kids. So I laid that out. I told them, ‘These are the hardest mornings to teach, but these are important mornings because you are living through this at the same time as every adult out there. Your parents are struggling with trying to understand the same exact things as you are, and as I am.’

I feel like we sometimes believe kids process things the same way (that) we adults do. And they don’t. I remember as a sixth-grader, when the Iran hostage situation happened, I could watch the news and I could hear conversations, but I didn’t know where exactly I could ask questions or get answers. I don’t remember too many teachers talking about it. And so there’s times where I feel like kids are trying to understand big issues on their own, and that’s difficult and they shouldn’t have to. They have the same worries when they hear about insurrection that everybody else should have.

SNN: What kinds of questions are students asking about Wednesday’s events?

MAZUREK: We started by filling in the gaps, but then some who clearly had watched a lot of the coverage had very specific questions: Why were (rioters) there? How did they get into the Capitol? What’s going to happen to them? Will the rioting continue to happen? Will they attack again? “Attack” came up a few times. Remember, they’re already living through so much uncertainty, pandemic-wise, and now this. So, I think a part of our job is to help them understand the moment, but also give them some assurances and honest information to help them process. Even though I may harbor my own fears, we are caretakers to these kids — they are our kids.

SNN: Are there any concrete tools you give students to help them work through this?

MAZUREK: I try to encourage discussion about how you discern quality information. I remind them about using multiple sources and not just grabbing hold of one thing you read on one post on one news source. You have to go find out if there are other places with the same (information). That also gives them a bit of control. Kids already feel a sense of powerlessness in many ways, and this gives them the tools to say, ‘I can be the one that starts questioning what I see.’

I also told the kids today, ‘this isn’t even 24 hours old. I can help you understand what I understand to be true as of now, but we may find out that’s not necessarily what happened.’ So, I frame it with a giant asterisk: “So far, what we understand is…” And then as a history teacher, I can try to put it in historical context. These kinds of things happen, and we as a country have lived through it. (The breaching of the Capitol) is very different because of the involvement of the president — that is truly unprecedented — but we’ve had other very, very, challenging, terrifying moments and we’re still here.

SNN: For teachers who don’t teach history or social studies, how can they tackle this?

MAZUREK: One of the things that we as educators have to really start looking at is the changing dynamic we have in our ability as citizens to engage with each other. Especially with the internet. I fear right now that if we don’t help kids navigate those waters, they are just wading into the troubling world that’s out there.

You might hear members of Congress refer to “my good friend on the other side of the aisle.” They argue with each other, but they try to present that level of civil discourse. I think some of that art is lost and I believe that’s a function of us getting away from civics. The concept of civil discourse, being able to have those conversations right now, is more important than ever. Right now, I would say we’ve got a national emergency in civics. If we want to see if we can turn this around, it’s got to happen.

And this is hard — we all know adults who can’t (engage in civil discourse) very well. So we have to start young. I think it starts out already in pre-K or kindergarten. A lot of these kids never had to deal with groups of 20 kids at a time on a regular basis (before starting school). How do they learn to function in a group? They’re teaching civics in pre-K.

SNN: What tips do you have for parents or guardians who want to reassure their kids, but don’t understand everything that’s happening in the news? How should they approach these conversations?

MAZUREK: Honesty is number one. if you don’t know the answer, you don’t have to know it right now. We have to be okay with saying, ‘I don’t know; that’s a really good question. Let’s find out together.’ It’s a great opportunity for both of you to learn, but also a good way of modeling the best way to find answers, by checking multiple sources and working through them together.

And then let the evidence lead you. You can’t be looking only for evidence that will fit how you want the world to be. A good historian, an educated citizen, doesn’t ignore contrary information, but gathers all the evidence. We have to model that.

I’ve found that kids actually respect when you say you don’t know something, because you’re showing your human side. We authority-type figures often want to keep ourselves in this elevated place. But if you can’t sit down with them and say, ‘I’m in the same place you are; I don’t understand. Let’s find out,’ you don’t get as far. And I think that that’s the best way to go forward.

CONNECT

10 tips for talking about news, politics and current events in school