Multi-district — On Fridays at lunch, sixth-grader Bryce Barry typically counts his “Be Tickets” outside the Lowell Middle School Be Store to redeem them for Jolly Ranchers.

Bryce and his peers earn the tickets as part of the school’s Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports framework.

“One was for being responsible. I was doing exactly what I was supposed to do and helping other people follow the rules,” he explained. “Another was for unstacking all the chairs, and one was because I opened the door for everyone even though I had my hands full with books and stuff.”

Bryce’s positive behavior doesn’t stop when he cashes in his tickets for candy. He shared his recent earnings with friends.

“They’re really trying to do the right thing, but they just have a hard time sometimes,” he said. “So, I’m being kind to them and rewarding them for their hard work.”

The ‘Why’ Behind PBIS

PBIS is a big term for a fairly simple concept: if students have a positive school climate and know what’s expected of them, they will do better academically.

Typical scenes in Kent County schools tied to PBIS programs involve students celebrating good behavior and taking ownership of expectations: they cash in their good-behavior tickets for prizes at school stores; they work together to set kid-friendly classroom rules like “no bullying,” and “don’t talk when others are talking”; and they hang posters and sing songs to remind each other to “be safe, responsible and respectful.”

Kindergartners learn expectations from the day they first enter the building, and they are consistent in classrooms, hallways, the playground and bus. That’s the key to PBIS: it’s reinforced everywhere at school.

“PBIS is leveling the playing field for all students and giving them opportunities for learning,” said Angie Stauffer, Duncan Lake Middle School assistant principal. “It’s a constant process of teaching them expectations and talking about them.”

With everyone on the same page, the focus can be on teaching and learning. “School is a place to educate and if we’re spending more time worrying about behaviors, we’re not focusing on academics,” Stauffer said.

PBIS, first implemented in Caledonia in 2012, emphasizes what students should be doing as opposed to reprimanding them for behaviors they shouldn’t be. The Michigan Alliance for Families identifies two different approaches for dealing with behavior problems in schools: one is that the child is a problem, and the other is that the child has a problem. PBIS affirms the latter.

‘When we, as adults, create the expectations for students without their input, we are not being culturally responsive.’

— Alex Kuiper, Godfrey Elementary dean of students

After teaching for 21 years, Stauffer said setting standards for positive behavior is not new, but PBIS is “changing the conversation.”

For example, she said, “A kid gets on the school bus in the morning and the bus driver uses the same language for conflict resolution as the ladies who serve lunch. It establishes consistency for staff and teachers to know how to address behavior issues.”

Dedrick Martin, superintendent of Caledonia Community Schools, attributes increased academic proficiency in math and English language arts, compared to a state-wide decrease over the last five years, to a positive district-wide culture created by PBIS.

In fact, the district was recognized at the state level for their work in Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, a framework that works hand-in-hand with PBIS to provide every student with a strong core curriculum and behavioral intervention.

As a way to further their efforts, Caledonia launched a new training for employees in Capturing Kids’ Hearts this summer. That curriculum is designed to equip educators with skills to build meaningful relationships, create a safe learning environment and respond to positive and negative behavior.

“One of the common things we hear is ‘Why would we reward students for things they should be doing?’” Stauffer said. “(We do it) because I’ve seen them change their behaviors. This is successful because we can actually see the improvements in their behavior traits every day.”

Teaching ‘Real-World’ Life Lessons

In Godfrey-Lee Public Schools, teachers and other staff members encourage elementary students to “go for the gold” through their PBIS program. Alex Kuiper, Godfrey Elementary’s dean of students, explained how establishing a routine helps students function better.

“We know student and staff behavior affects learning,” he said. “One of the things PBIS does well is focus on routines and procedures in school to create consistency, taking the cognitive load off the student.”

If students learn to expect consistent responses from teachers and staff members, he said, they can adjust their behavior accordingly and encourage their peers to do the same.

‘I like to ask kids to play and instead of disincluding them, including them.’

— Belmont Elementary third-grader Keegan Poulson

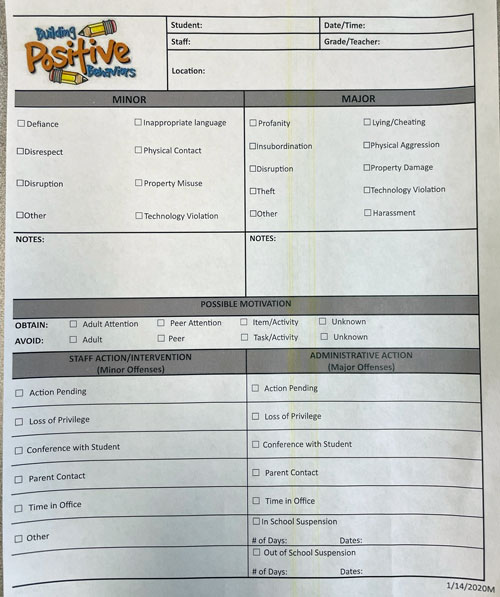

Audra Holst-VanNoord, Lowell Middle School’s coordinator of student support, said PBIS’s consistency provides enough direction for most students to know what’s expected of them. About 97% don’t require additional behavior support, but for those who do, staff members work with them individually or in small groups.

“The one thing PBIS is not is a complete lack of consequences,” she said. “If you do the right thing, there are rewards. If you don’t, there is a consequence, just like real life.”

An App for PBIS

A new app called PBIS Rewards is adding to the fun in Caledonia, where teachers award students with points for good behavior.

“Every staff member has the app on their phone and if (they) see a student picking trash up off the floor, they can reward them points on the app for being a good example of a responsible person,” Stauffer said.

Points trade in for tickets and, similar to Lowell Middle School, students can use their tickets at the school store for prizes. Points can also be privately viewed on students’ accounts to avoid publicly comparing or calling out those who have fewer points.

‘School is a place to educate, and if we’re spending more time worrying about behaviors we’re not focusing on academics.’

— Angie Stauffer, Duncan Lake Middle School assistant principal

At Belmont Elementary in Rockford, Principal Shannon Ouellette said creating a positive learning environment is all about “catching kids doing the right thing.”

Third-grader Keegan Poulson was caught doing the right thing exactly eight times in October. He received Ram Pride tickets for things like cleaning up balls on the playground and making other kids in his class feel included.

“I like to ask kids to play and instead of disincluding them, including them,” Keegan said.

What good behavior looks like at school: “Being kind and not being disrespectful” to your friends or teachers, he said.

Encouraging Safety & Equity

Godfrey-Lee’s PBIS program has evolved to better meet the needs of the student population, which is 80% Hispanic, according to MiSchooldata.org. The district uses restorative practices, which focus on resolving conflict and healing relationships.

“PBIS started in a way that is very White-centered and looking at the data, (punishments and suspensions) are given disproportionately to certain races of students over others,” Kuiper said. “Moving toward ‘consequences’ and away from ‘reward and punishments’ models real life.”

Including student and parent voices alongside teachers’ through the district’s PBIS committee also is part of making school a safe and positive experience.

“When we, as adults, create the expectations for students without their input, we are not being culturally responsive,” Kuiper said.

Comparing student behavior this school year to last year, Duncan Lake Middle School is seeing fewer write-ups in the first month alone. Lowell Middle School is seeing a similar trend.

“Of course, kids are still being kids,” Holst-VanNoord said. “Nothing is perfect, but it’s been a cool framework to put into place and see affecting students.”

The benefits of PBIS are obvious to students as well.

Said Bryce: “It makes it a much safer environment to learn, because everyone knows what they should be doing and can be held accountable.”

Meghan Gracy and Allison Poosawtsee contributed to this story