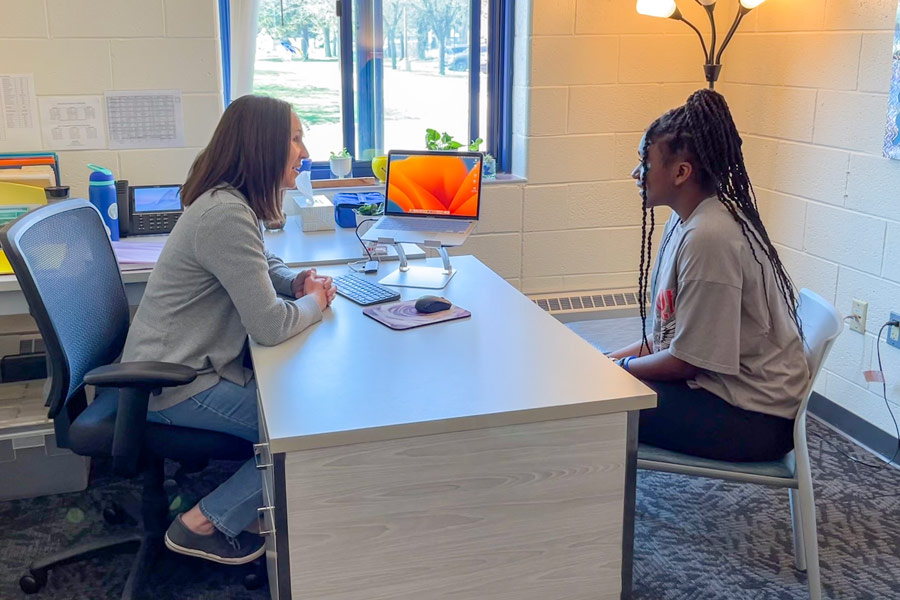

Multiple Districts — On a busy afternoon in the front office at Lowell Middle School, school secretary Kendra Dixon is clearly juggling a lot. As she buzzes someone in at the front door, answers a parent phone call and watches students between periods stream into the office with various questions and complaints, she adds another task to the mix: mental health triage.

When a troubled student walks in and can’t seem to voice her need, Dixon does her best to ascertain the issue at hand. It’s clear that the student is overwhelmed, and together with Dixon she makes a plan to take a short walk through the school’s bright, freshly-painted hallways.

As students like the Lowell middle-schooler enter the classroom with more and more mental health concerns, districts in Kent County are grappling with just how to address what the U.S. Surgeon General’s office has deemed a full-blown crisis. And with an influx in state funding via special grants approved by the Michigan legislature in July 2022 to ramp up mental health programming in the post-pandemic era, each district is having to decide where to put those dollars.

What is 31aa?

In July 2022, the Michigan legislature approved new funding for schools across the state to improve student mental health. The funds were designated to be used in these four ways:

1. Hiring or contracting for support staff for student mental health needs, including, but not limited to, school psychologists, social workers, counselors and school nurses

2. Purchasing and implementing mental health screening tools

3. Providing school-based mental health personnel access to consultation with behavioral health clinicians to respond to complex student mental health needs

4. Any other mental health service or product necessary to improve or maintain the mental health of students and staff

Sobering Data on Youth Mental Health

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, national surveys to capture youth mental health trends noted major increases between 2009 and 2019 in regards to depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts. This was enough to cause Surgeon General Vivek Murthy to issue a warning about the “devastating effects” mental health issues are having on youth mortality rates.

“In 2019, one in three high school students and half of female students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an overall increase of 40% from 2009,” Murthy wrote in the advisory.

Then in 2021, in the middle of the pandemic, more than 4 in 10 students surveyed nationwide by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported they felt persistently sad or hopeless; nearly one-third experienced poor mental health.

Michigan-specific data is equally sobering: 2019 data demonstrated that death by suicide is tied with unintentional injury for the top leading cause of death for 10-14-year olds, according to the CDC and the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Girls are especially at risk, with one in three female youth reporting seriously considering suicide in a 2021 survey.

By approving funding for Michigan’s Section 31aa student mental health grants, state legislators hope to at least slow, if not reverse, these trends at a local level. The grant program disperses money to districts that apply for the purposes of hiring or contracting mental health support staff to meet student needs.

“There’s really an emphasis from the Michigan Department of Education for students having the mental health supports they need coming out of the pandemic,” said Jeff Owen, Kelloggsville Public Schools’ director of instruction.

Still, the responsibility lies with district administrators to determine what sort of supports best suit their students, staff and community.

How Should Schools be Involved?

In Lowell Area Schools, Assistant Superintendent Dan VanderMeulen is part of a district-wide mental health team in charge of developing plans to spend these new monies from the MDE. He said in recent years it’s become clear that supporting students holistically will help them do better in the classroom. Yet there remains some debate on how far schools should go to provide mental health services.

“Are schools responsible for providing psychotherapy on a long-term basis? Where do the school’s responsibilities end and the parents’ responsibilities start?” VanderMeulen said.

Even with those questions in mind, he said LAS is making significant investments to support students by working with local counseling offices to find the help they need to thrive.

“We’re talking about expanding our partnerships with local agencies for referrals. Especially for families who don’t have insurance, or who do but their coverage doesn’t fully cover therapy,” he said.

‘Schools have a huge responsibility in the community to do the best we can … to create responsible and respectful people — and mental health is part of that.’

— Dan VanderMeulen, assistant superintendent, Lowell Public Schools

Increased support for student mental health in Lowell will also include funding a new internship for a school psychologist who is completing their doctoral degree in the field to assist the district’s two existing school psychologists.

Despite ongoing debate amongst educators, parents and community members about the role of schools in supporting students beyond academics, VanderMeulen points out that mental health is key in developing future citizens.

“Schools have a huge responsibility in the community to do the best we can, during the time we have students, to create responsible and respectful people — and mental health is part of that,” he said.

From Triage to Full Support

In Kelloggsville Public Schools, administrators are planning to use the approximately $250,000 it received from the MDE grant to hire more counselors and mental health clinicians, in an effort to better help students deal with issues inside and outside of the classroom.

Counselors, currently staffed at a level of at least one per building, provide student support for mainly school-related topics such as grade improvement. The district’s three mental health clinicians, on the other hand, are licensed therapists and social workers who meet regularly with a caseload of specific students.

‘(Students) are realizing, when they’re struggling, it’s OK to talk to someone about it. They don’t just have to keep it in.’

— Laura Kuperus, Kelloggsville Middle School counselor

By the end of the 2024-25 school year, Kelloggsville plans to have a total of five mental health clinicians, contracted by Grand Rapids-based Family Outreach Center, and nine licensed counselors to support its students.

Kelloggsville Middle School Counselor Laura Kuperus said younger people have become more aware of mental health issues in recent years and discussing it is becoming less stigmatized.

“They’re realizing, when they’re struggling, it’s OK to talk to someone about it. They don’t just have to keep it in,” she said.

This has created more demand for the counseling office. An average of 50 students a week stop by Kuperus’s office to talk about everything from their grades or prepping for a career, to heavier topics such as mental struggles.

Although counselors are not licensed therapists, she said they have sometimes had to fill that role in absence of another staff person, being someone students can talk to about anything when needed.

“Sometimes we do become that person who is checking in on them every week,” Kuperus said.

She is excited for the district to hire more people to fill that gap and help focus on students’ mental health.

“I think it’s amazing because it’s very needed. I feel like there’s so many more things we could be doing and we kind of have to triage and deal with the things that come at us right away,” she said.

Rockford Public Schools Has a Plan

Even before the pandemic began, Rockford Public Schools was moving to address the youth mental health crisis. In 2019 the district hired David Jangda, a clinical psychologist with experience working with youth at Pine Rest, to develop a comprehensive approach to supporting students.

‘My biggest thing is relationship-building with parents. I tell them, ‘I respect you as parents (and) it’s not my place to tell you how to parent your children. I’m just here as a resource.’

— David Jangda, mental health liaison, Rockford Public Schools

Jangda’s task was clear: create a plan that everyone in the district can use when students come to school with acute or chronic mental health concerns. Keeping students from spiraling into self-harm requires help from everyone in the school environment, he said.

“One of the best ways we can prevent a kid from going down that road and making an attempt on their life is a trusting adult in the school. It’s a coach, a choir director, it’s one of our security officers. We’re all eyes and ears and that’s why we train all of our staff. Secretaries, our bus drivers, our parapros … They need to know what to do if they hear some of this,” he said.

Amid a state-wide shortage of mental health professionals, Rockford is dedicating its nearly $900,000 in 31aa grant monies from MDE to provide more competitive compensation packages to its psychologists, social workers and other mental health support staff, said Mike Cuneo, assistant superintendent for finance. Doing so will enable the district to continue the plans Jangda has put in place.

A Multi-Tiered Approach

Jangda’s mental health plan, created in collaboration with staff across the district, is grounded in research that says that identifying and treating youth mental illness early can not only save lives, but also prevent school-based violence and boost graduation rates.

Rockford’s approach begins with clear plans at the building level to organize a support process for students struggling with a mental health concern. A student could self-report an issue, but a teacher, parent, security officer, peer or social worker could report it, too.

“If it’s a low-level issue, who do (they) contact? If it’s a full-blown crisis, where a student is threatening to hurt others or themselves here at the high school, we also know what to do and who to call,” said Jangda of the plan.

Knowing the process helps all staff know when it’s time to go into crisis mode, and also when the concern doesn’t warrant that kind of response, he said. Plus, it ensures that concerns are never dismissed or given a wait-and-see status.

In an instance where a student’s mental health concern warrants a full-blown crisis response, Jangda and his colleague, new elementary mental health liaison Colton Cnossen, get involved immediately.

“A lot of my work is interviewing kids and doing triage, talking to parents and getting consent — making sure they’re OK. And then a lot of my time is spent navigating through resources clinically, so it could be (working with) Helen DeVos (Children’s Hospital) or working with Pine Rest or Forest View Hospitals,” Jangda said.

Parents are Kept in the Loop

Traditionally, Jangda said, schools did not provide mental health resources and so understandably, parents may have questions about the work that he does with students.

“Nowadays, there’s just so much going on in our kids’ lives,” he said. “We think it’s advantageous for our families to have these resources because, otherwise, where are you even going to start? (They might ask) ‘What’s going on? Why can’t I get my kid out of bed in the morning? Who do I call? Are they safe?’”

As a rule, he involves parents or guardians at every stage of crisis response.

“My biggest thing is relationship-building with parents. I tell them, ‘I respect you as parents (and) it’s not my place to tell you how to parent your children. I’m just here as a resource: these are my thoughts, this is what we’ve noticed and now here are some things you can do,” he said.

Working to Achieve Balance

It’s too early to see the full impact of the district-wide mental health plan on students in Rockford, so in the meantime, Jangda keeps the sobering data from the Surgeon General regarding youth mental health in mind as he works with staff and students.

“Those statistics are what motivate me — of the students who are taking their own lives. That’s why we’re doing what we’re doing,” he said.

He’s optimistic that schools, together with parents and the broader community, can help kids manage stress and learn to be resilient from a younger age.

“We have these amazing kids who work so hard and do all these things like sports, music, the arts, but now we’re talking to kids about balance. We’re super happy that … you want to achieve these things in life, but at the same time, this marathon we have to jog. We can’t sprint it.”

Reporter Sean Bradley contributed to this story

Why a Crisis?

Is the pandemic to blame for the youth mental health crisis? Is social media and other mobile technology? Is this really a new crisis, or has it been there all along and youth are simply more comfortable now to voice their challenges?

Lowell Middle School Counselor Katie Erickson tries her best not to blame the crisis solely on phones or the pandemic, but rather notes that students are coming to her office — sometimes multiple times a day — because they’re coming to school with fewer coping skills than they used to.

Some of this may be attributed to the pandemic, she said while describing an atmosphere during the 2021-22 school year where ambulances were called to the school to address acute mental health issues at alarming rates. This school year has been better, Erickson said, but still, Google form requests from students to visit her office had already tallied 400 as of early spring 2023.

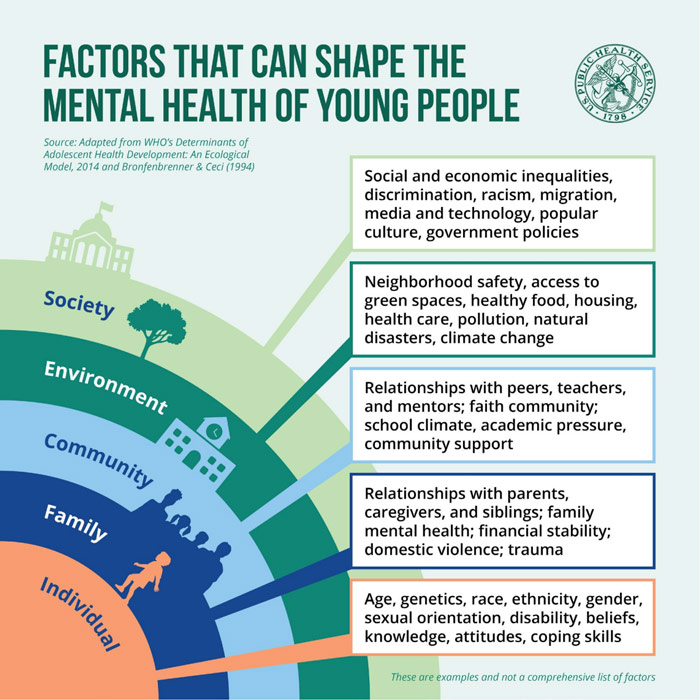

In his advisory report on youth mental health released in December 2021, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy points to the complex factors contributing to increased risk for young people:

“While some believe that the trends in reporting of mental health challenges are partly due to young people becoming more willing to openly discuss mental health concerns, other researchers point to the growing use of digital media, increasing academic pressure, limited access to mental health care, health risk behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and broader stressors such as the 2008 financial crisis, rising income inequality, racism, gun violence, and climate change.”

Read more from Kent County schools:

• How safe do you feel in your school?

• Working — and studying — for a living