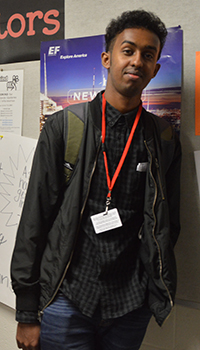

Note from the author: I met Arafat Abdikarim Yassin last February while visiting East Kentwood High School to write about the school’s refugee population. When I asked him if I could write his story, he said he wanted to write his own, but needed help. So I gave him help, and Arafat quickly became a dear friend to me, my husband, Ignazio, and our children, Rocco, 12 and Lena 10. Here is the story he wrote, which he plans to expand in the future.

Over the months, he also became more comfortable with my writing about him. So I recently followed him around school for a glimpse into the day in the life of a refugee from Somalia. Arafat is working to graduate in May, just two and a half years after arriving in the U.S. with little formal education.

His story begins: “My name is Arafat and I am 18 years old. I was born in Mogadishu, Somalia.”

From that basic introduction begins the journey of a boy who grew up in the horn of Africa, a land bordered by beautiful beaches, its people influenced by tradition and strong cultural connections. A child of war, his memories are filled with love for his family but are tinged with blood.

He grew up with an extended family, including 24 siblings, who worked together like a village, sharing food and laughter, respect for elders and celebration through dance.

“What I most, most, most miss is when the whole family comes together,” said the East Kentwood High School senior.

| Editor’s Note: Places of Refuge is a series focusing on refugee students and their journeys, their new lives and hopes for a future in West Michigan, and the many ways schools and community organizations are working to meet their needs. |

The refugee, who left his family behind, is now working his way through high school. He has made it his mission to be successful in the United States, give back to his family, and share kindness with everyone he meets. He asks lots of questions, loves to share his perspective on current events and his faith, and writes down English words on his phone as he learns them.

He has come a long way from when he arrived two years ago speaking little English, malnourished and meeting white people for the first time. Arafat, who turned 19 in January, arrived in the U.S. alone. His mother and several siblings remain in a Ugandan refugee camp. Arafat lost touch with them for almost two years before receiving a call from his mother, with whom he now has regular contact.

He has shared his apartment with several other Somali refugees, all who escaped the war-torn country. He receives money through Grand Rapids-based Bethany Christian Services for rent, food and clothes.

“I’m transformed and that’s the best thing,” he said. “I’m having a good life. I’m free from pain, fear. I’m not helpless anymore. I see a future.”

But he hasn’t forgotten the past. “Dark is my enemy and sometimes it’s hard to get enough sleep. Screams never go away. Memories don’t ever go away.”

And as of this week, he confronts a new fear: that he may not be able to reunite with his family. They have applied to immigrate to the United States — an option closed for now by President Donald Trump’s travel ban on Somalia and six other countries.

A School Day in the Life

Arafat wakes up in his first-floor apartment at 5:21 a.m. He has lived there for a year. The building is dank and spartan but with signs of maintenance, like fresh paint on the walls. In the yard outside, fast-food wrappers, containers and trash are strewn about. The smell of cigarettes and marijuana lingers in the entryways. Window screens are torn — children’s eyes often peering out from inside — and the place gets noisy, even in the wee hours of the night.

The first thing Arafat does after rising is pray, kneeling face down on the floor facing Mecca, Islam’s holiest city. It is the first of five times he will pray that day as a Muslim, devout in his faith. Because he is a busy high school student, he doesn’t always do the traditional prayer ritual, but prays silently. During Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, he fasts, even giving up water from dawn to dusk.

Prayer and faith are what kept him alive, hesaid, and provided him with strength after he left Somalia, where his family was targeted by a militant terrorist group. He was eventually brought to the United States and received refugee status.

“I’m so grateful and thankful to God. I used to say, ‘Why me?’ But blaming is the same as making more problems. Pain becomes hard to eliminate but God was with me.

“Here I am today, so I shall be thankful. I feel like I was doing a test and I passed that test.”

He is well on his way to completing high school in two and a half years, and graduating from East Kentwood High School in May. His current GPA: 3.6.

At 6:30 a.m. Arafat catches The Rapid bus outside his apartment complex for the 25-minute ride to school. He spends time in the media center, perfecting his homework before heading to his first-hour class, U.S. History, at 7:40 a.m.

Telling a Traumatic Tale

Next is geometry and English for English-language learners. He listens to peers, also immigrants from around the globe, present their memoirs. He read his narrative to the class the day before, recounting how he got a scar on his elbow. It was caused by members of the terrorist group al-Shabab, who entered his home to murder his family they had marked as infidels.

The story includes this memory: After the men killed his grandfather, Arafat came out of his hiding spot to check on his mother. The men were still there, including one that hit him hard. “The man was inside of the room holding his rifle,” he wrote. “He swung it around, hitting me with its back end in the back of my arm, cracking my elbow. I immediately started vomiting. Suddenly, they ran, disappearing into the night.”

At 11 a.m. Arafat joins his friends in the cafeteria for lunch. They are refugee students from Pakistan, Ivory Coast, Afghanistan, Eritrea and Somalia. A welcoming bunch, they are excited to talk about themselves.

After lunch, Arafat takes the bus to Kent Career Tech Center, where he spends his afternoons learning about marketing and entrepreneurship. He’s completed a press release and marketing plan, and has learned it’s a different world when it comes to business here. At 9 years old, he was peddling water and fried food called samosa on the streets.

Now, at the Tech Center, he works with students from several Kent County districts, Their interest is piqued when they learn he is a Somali refugee. They ask him about the foods he eats, where he comes from.

Working Toward College

Class ends at 2 p.m., and Arafat returns home at 2:30. His caseworker, Maribel, is there for a home visit. He tells her school is going well; his bus pass is expiring the next day; and he plans to get a job after he completes geometry class, which is difficult for him. He needs to get started on his Free Application for Federal Student Aid, to receive financial aid for college.

At 3 p.m Arafat stops at the apartment next to him to visit an 18-year-old Somali woman, also a refugee, and her two-month old baby.

At 3:55, Arafat arrives 10 minutes late for a dentist appointment, at a place that works with Medicaid patients, to get a cavity filled. His driver, me, is the reason he is late. The lady at registration tells him he is probably too late. She checks, returning to say, “It’s your lucky day. But be more aware of the time.” She taps her watch.

Arafat spent the evening with me and my family, eating dinner and going to the mall to get a winter coat. He then returned home to do his homework and go to bed.

Arafat plans to attend Grand Rapids Community College next school year, working toward degrees in business and health care. His ultimate goal is to become a urologist.

After his arrival inthe U.S., he struggled with depression and anxiety, at first not wanting to connect with anyone.

“I realized a lot of things after being through therapy,” he said. “(My therapist) made not be silent anymore and speak out. Speaking about your life helps you feel less stress. It’s better than being silent.”

After Trump’s Order, Sadness and Fears

He chose not to be silent after the stroke of a president’s pen threw his family into turmoil.

I checked in with Arafat following President Donald Trump’s executive order last week for a travel ban affecting seven countries including Somalia. Arafat’s mother and eight siblings were nearly to the end of the vetting and interview process to immigrate to the United States when Trump signed the order.

“It’s really sad, to be honest, because we all have a dream,” Arafat said. He now fears he won’t be reunited with his family for a long time and worries about their well-being, including a brother who is severely disabled.

He said the tense political climate has given him a sense of increased uneasiness. When people ask him where he is from, he is afraid to tell them. He said he wants people to know that he has been a direct victim of the type of terrorism people fear.

“I am Arafat. I’m a Muslim. I am not a terrorist and I will never be a terrorist.”

The protests at the Gerald R. Ford International Airport and around the country over the weekend gave him and his friends some reassurance.

“When I saw all of these people protesting I felt healing,” he said. “Together we are strong. All the Muslims were proud of that.”

CONNECT

SNN Story on KW Refugee students