For more than 150 years, they’ve been turning out heroic figures at the former Grand Rapids Central High School – now Innovation Central High.

But this school season, the bar was raised when a humble soldier limped across Central’s threshold to join the ranks of notables such as astronaut Roger B. Chaffee, First Lady Betty Ford, U.S. Senator Arthur Vandenberg and pro athletes like Buster Mathis and Terry Barr.

Unlike his predecessors, however, Lt. Col. Bryan Forney showed up as a schoolteacher, moreover, one who is arguably handicapped and disfigured — missing his left arm and several fingers on his right hand. More than half his taut body is covered with red and purple scars, splotched remnants from third-degreeburns he suffered in a horrific helicopter crash.

But make no mistake about it. He is here to teach science and math. And though he retires at the end of the school day admittedly “wiped out” delivering lessons aboard wobbly legs that both sport braces, it’s arguably nothing compared to what he’s been through for his country.

“I’m thinking to myself, ‘Who is this guy?'” Central High Principal Mark Frost was recalling of the day he interviewed Forney for an open post at the venerable school on Fountain Street NE.

“So then I YouTubed him.”

Frost’s voice breaks a little.

“And then I’m like, ‘I gotta have this guy.'”

‘So This is How it Ends’

To know this Marine-turned-schoolteacher’s story, you must go back to 2013, on a February day atop a mountainside cliff in Phitsanulok, Thailand. That’s where Lt. Colonel Bryan Forney – second in command of an entire helicopter squadron – was conducting a training flight.

At a critical point, a blade from the craft’s aft rotor head struck a tree. The chopper broke apart and went into a free fall. The crew was able to evacuate. Forney was pinned in the cockpit.

“I was saying my goodbyes,” he remembers. “I couldn’t do anything with my left arm; it was basically crushed. The way we hit … I couldn’t get out the door. I thought to myself, ‘So this is how it ends.'”

In the moment, Forney not so much trembled for his life as he felt he’d let his wife and three kids down. Throughout his entire military career – in peacetime and in harm’s way both – he’d promised them he’d always come back. And now – on what had been scheduled as his very last training flight, the irony of ironies was that he was going up in flames.

“Here I was, messing up.”

Somehow, and in the nick of time, his crew chiefs were able to free him. The rescue by another aircraft took nearly four hours. And the long road to recovery lay ahead: Five torturous months in the hospital, involving surgery after surgery. Not to mention untold number of hours of rehab to contend with the loss of an arm, a shoulder blade broken clear through, a fractured humerus, both kneecaps rendered virtually useless, and burns to more than 54 percent of his body.

Watching videos of his comeback is not for the faint of heart. The tubes, the grafts, the lesions; the grunting of a man trying to take a single step. The sheer amount of time required to resurrect himself from near death. Captured digitally, while surrounded not only by therapists but a cheering wife and kids, it’s a lesson in humility. And how to not sweat the small stuff.

Class Time

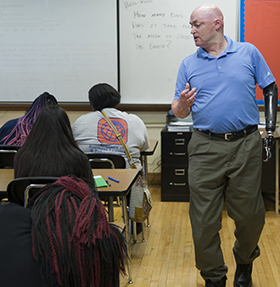

It is 9:45 a.m. Time for Algebra II.

“Let’s get situated” he says to 16 students. “I want to give you a quiz I just know you’re all looking forward to.”

A chorus of groans.

Before administering it, he performs bit of a review at the front of the room, talking about the box plot and its disadvantages. To lighten things up at one point, he asks a student in the back row who wears an Ohio State University T-shirt, “Are you really an Ohio State fan?” The kid nods.

Says the Colonel: “Your grade just plummeted!”

Throughout the hour, he sometimes leans on a prosthetic arm for balance. It terminates in a pair of hooks that he controls through messages sent by his upper arm. When not upright in place, he’s walking the room, herky-jerky thanks to the braces and lasting injuries.

He addresses the students in one of three ways: By their name. By “sir.” Or by “ma’am.”

After the quiz, they discuss correct answers, reviewing mean and median and mode. Someone frets over what a failed grade this day means. His answer: “If you fail the quiz, that tells you what you have to work on for the final.” He reminds them this is a 10,000-point class, so plenty of time to fail but then rebound.

He notices that not enough of the students are taking notes. He reminds them it’s a good idea, even though “I have a beautiful voice that will lull you all to sleep. I put my wife to sleep all the time when I start talking.” He smiles. “But you need to take notes.”

The hour passes quickly. “See you tomorrow,” he says, then singles out the OSU fan: “Even though you’re a Buckeye,” the Colonel says, “have a good day.”

Secretly Driven to Teach

A native of Okemos, the Colonel – now 42 — graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis directly after high school with a degree in aerospace engineering, then embarked on a career with the U.S. Marines. He holds a master’s degree in applied physics.

He says that even while serving in the military, “My dirty little secret was that I wanted to be a science teacher. From the time I taught at the Academy, I always just enjoyed helping guys figure stuff out. I figured that my entire adult career had been serving my country. Next, I wanted to serve my community, defending democracy by turning out the best possible citizens coming out of high school.”

After recovering from his accident, the Colonel served as a consultant with the Military Burn Research Program, then, among other roles, as operations officer of a Wounded Warrior detachment in San Antonio, Texas. It was during his recovery that he also became certified to teach high school science and math.

Upon his formal retirement from the Marines this past summer, he signed on at Innovation Central High at a starting teacher’s salary of about $41,000. While he didn’t know all the jargon a teaching candidate often brings to the interview process, it wasn’t lost on Principal Frost that “this gentleman brings gifts you don’t see from someone just coming out of college — the things embedded in a lifetime of living that he brings along with his skill sets.”

He and wife Jennie live in the Lowell area with their three children – William, 14, Anna, 10, and James, 6. The oldest attends Lowell High; the other two Murray Lake Elementary.

Among the most difficult things the Colonel has had to do is adapt to becoming a receiver of services rather than the proud provider. Watching as his wife served as his caregiver was a blow to his pride, and it took a long time for him to become used to a new normal.

First-year Challenges, and More

Stepping up to teach has not been a cake walk. First, there are the physical limitations that make everything just more difficult. Then there’s the burden every first-year teacher endures of preparing lesson plans from scratch.

Three weeks into the school year, he was asked how many times he’d had a chance to cool off in the teacher’s lounge.

His answer: “I haven’t ever been to the teacher’s lounge.”

By all accounts, he has earned the respect of his students. Says Ethan McDonald, a senior: “A great, integrity-filled man. A leader who cares about kids. And he cares about teaching.” He adds, “Don’t judge a book by its cover.”

As the Colonel teaches, he also learns. About himself. About what he’s gone through. And about expectations for the future.

Asked what he considers a productive day, he mulls it a moment, then answers like this: “Well, like I used to tell the guys: If nobody’s tried to shoot me … and I haven’t been to a friend’s memorial service … and I get to go home to my wife and kids. That’s a good day.”

Which isn’t to say he doesn’t harbor regrets. “I do mourn the loss of things. Like flying again. And the simple things. Like getting out of bed quickly at night to go to one of the kids. I can’t run, so I can’t play football or softball. It’s hard to even play a game of catch with the kids. That sort of thing.”

Then he takes a half-step, leans his hooked hand on an empty desk for support, and smiles wryly.

“But I can teach.”